Second World War

The Second World War (1939–1945) transformed Canada’s place in the world. Where the First World War had tested a young Dominion’s resolve, this conflict demanded sacrifice on an even larger scale. More than one million of Canada’s population of 11 million served—soldiers, sailors, aircrew, nurses, and merchant mariners—while millions more supported the war effort at home. Canada entered the war as a largely rural country on the periphery of the world political stages and emerged with an international reputation for endurance, skill, and innovation. Canadian forces fought in every major theatre: in the skies over Europe with Bomber Command, across the Atlantic safeguarding vital supply lines, and on land from Hong Kong and Sicily to Normandy and the Scheldt. On 19 August 1942 at Dieppe, Canadians bore the brunt of a disastrous raid; on 6 June 1944 at Juno Beach, they helped crack open Hitler’s Atlantic Wall. At home, the war mobilized the country on an unprecedented scale. Skies buzzed with the yellow training aircraft of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, as over 130,000 air personnel, including nearly 73,000 Canadians trained for the air forces. Civilians worked in factories, shipyards, and munitions plants, served as drivers and clerks, ran farms and businesses, planted “Victory Gardens” to offset the rationing of food, and kept families going under wartime strain. The human cost was immense: more than 45,000 Canadians were killed and over 55,000 wounded, while thousands more were taken prisoner or lost at sea. Yet the end of the war also brought new resolve. Determined to do better than after 1918, Canadians supported a far-reaching Veterans Charter that offered education, housing, and benefits to help rebuild lives. Many returned home with unseen wounds to a country reshaped by six years of global conflict, where remembrance and rebuilding became collective responsibilities.

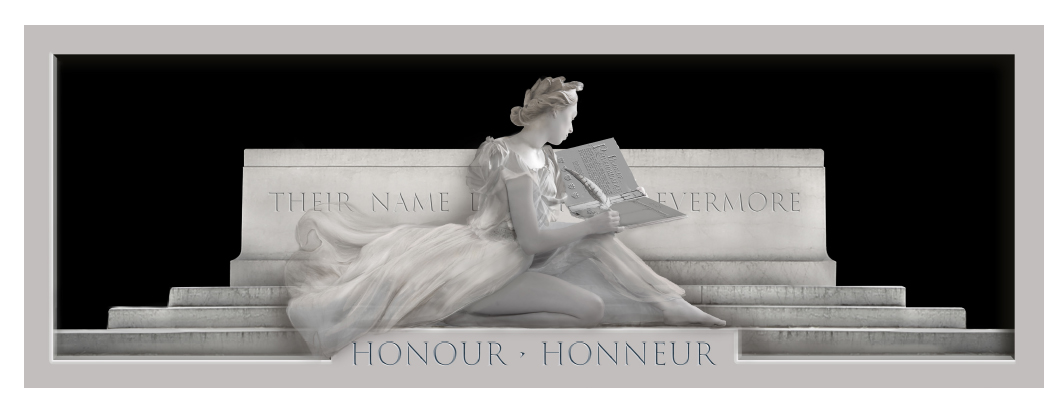

The panels on this column trace this arc: the separation and sacrifice felt in Canadian homes and on assault beaches; the perilous air and sea lifelines that sustained victory; and the intimate costs of care, captivity, and burial. This column honours the more than 45,000 Canadians lost in the war, whose names are recorded in the Books of Remembrance for the Second World War, Newfoundland, and the Merchant Navy in the Peace Tower, Ottawa.

Separation and Sacrifice

By the middle years of the Second World War, as Canada’s commitments widened overseas, Canadians were fighting and dying across multiple fronts, from the grey waters of the Atlantic to the villages of France. For many, service overseas meant years away from home and the constant shadow of uncertainty, as families waited for letters or telegrams that might bring news of life, injury, or death. These long separations reshaped family life across the country: mothers managed households and farms alone, children grew up without fathers or older brothers, and the rituals of daily life carried on beneath the weight of absence. Sacrifice in this war was measured not only on the battlefield but in the quiet endurance of those left behind. Kitchens and living rooms became places of waiting. Calendars marked with birthdays and holidays served as reminders of missing faces, while news from the front arrived slowly, sometimes with devastating finality. For many families, grief was private and unspoken; for others, it became communal, shared across workplaces, schools, and neighbourhood streets.

This pillar also traces the risks borne by those who served. In August 1942, nearly 5,000 Canadians were committed to the Dieppe Raid, an ambitious Allied assault on German-held France. Within hours, there were 3,367 Canadian casualties, including 916 killed and 1,946 taken prisoner, and communities at home carried the weight of that collective loss. Two years later, on 6 June 1944, Canadians returned to France on D-Day, landing at Juno Beach as part of the largest seaborne invasion in history. For some, it had been nearly four and a half years since they had seen home, more than 50 months since the first Canadian units sailed for Britain in 1939. Facing fierce resistance, 359 Canadians were killed on D-Day; total Canadian casualties were 1,074. Over the Normandy campaign, more than 5,000 Canadians were killed, yet their determination opened the path to the eventual liberation of Western Europe. With these images, themes converge. Together, they remind us that separation and sacrifice were shared across oceans, carried both by those who served abroad and by those who waited, worried, and endured at home.

The panels on this column trace this arc: the separation and sacrifice felt in Canadian homes and on assault beaches; the perilous air and sea lifelines that sustained victory; and the intimate costs of care, captivity, and burial. This column honours the more than 45,000 Canadians lost in the war, whose names are recorded in the Books of Remembrance for the Second World War, Newfoundland, and the Merchant Navy in the Peace Tower, Ottawa.

Separation and Sacrifice

By the middle years of the Second World War, as Canada’s commitments widened overseas, Canadians were fighting and dying across multiple fronts, from the grey waters of the Atlantic to the villages of France. For many, service overseas meant years away from home and the constant shadow of uncertainty, as families waited for letters or telegrams that might bring news of life, injury, or death. These long separations reshaped family life across the country: mothers managed households and farms alone, children grew up without fathers or older brothers, and the rituals of daily life carried on beneath the weight of absence. Sacrifice in this war was measured not only on the battlefield but in the quiet endurance of those left behind. Kitchens and living rooms became places of waiting. Calendars marked with birthdays and holidays served as reminders of missing faces, while news from the front arrived slowly, sometimes with devastating finality. For many families, grief was private and unspoken; for others, it became communal, shared across workplaces, schools, and neighbourhood streets.

This pillar also traces the risks borne by those who served. In August 1942, nearly 5,000 Canadians were committed to the Dieppe Raid, an ambitious Allied assault on German-held France. Within hours, there were 3,367 Canadian casualties, including 916 killed and 1,946 taken prisoner, and communities at home carried the weight of that collective loss. Two years later, on 6 June 1944, Canadians returned to France on D-Day, landing at Juno Beach as part of the largest seaborne invasion in history. For some, it had been nearly four and a half years since they had seen home, more than 50 months since the first Canadian units sailed for Britain in 1939. Facing fierce resistance, 359 Canadians were killed on D-Day; total Canadian casualties were 1,074. Over the Normandy campaign, more than 5,000 Canadians were killed, yet their determination opened the path to the eventual liberation of Western Europe. With these images, themes converge. Together, they remind us that separation and sacrifice were shared across oceans, carried both by those who served abroad and by those who waited, worried, and endured at home.

External Links:

Second World War Book of RemembranceNewfoundland Book of RemembranceMerchant Navy Book of Remembrance

Library and Archives Canada / C-014160

On 19 August 1942, nearly 5,000 Canadians alongside British Commandos and a small contingent of US Rangers took part in Operation Jubilee, the raid of Dieppe, France. The aim was to seize and briefly hold Dieppe’s port, destroy coastal defences and infrastructure, and gather intelligence.

The raid became a disaster. At Puys, the Royal Regiment of Canada was caught beneath pre-sighted fire from the cliffs, suffering devastating losses. At Pourville, the South Saskatchewan Regiment briefly gained ground before being forced back. On the main beaches, the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, the Essex Scottish, and the Fusiliers Mont-Royal landed below fortified German positions, trapped on open shingle with little cover. The approach became, in survivors’ words, a “shooting gallery.” The 14th Army Tank Regiment (Calgary Regiment) launched 27 Churchill tanks in support of the infantry. Only 15 reached the seawall; beyond it, anti-tank obstacles blocked entry into the town. Forced back, the tanks provided covering fire for the infantry before being destroyed or abandoned on the beach. None returned; all crews were killed or captured. Casualties were staggering: 916 Canadians killed, 1,946 taken prisoner: 3,367 in all. While Dieppe’s costly lessons helped to shape Allied planning for D-Day, debate continues over whether the lessons-learned justified the human price paid that day.

This image, taken by a German military photographer after the battle, is both propaganda and record. The bodies of two fallen soldiers were deliberately positioned on the shingle for effect, the rear one believed by some to be a U.S. Ranger, underscoring German claims of total Allied defeat. Behind them, a Churchill tank lies immobilized, its tracks sunk into loose pebbles. To the right, a landing craft burns, smoke curling skyward. Beneath the staging, however, the tragedy is real. These men died here, alongside hundreds of others, in one of Canada’s bloodiest single days of the war. The wreckage—armour, landing craft, and human life—captures both the human cost of Dieppe and the way its meaning was manipulated: a failed raid turned into a symbol, its lessons written in blood, its consequences carried forward to the Allied return to France on 6 June 1944.

The raid became a disaster. At Puys, the Royal Regiment of Canada was caught beneath pre-sighted fire from the cliffs, suffering devastating losses. At Pourville, the South Saskatchewan Regiment briefly gained ground before being forced back. On the main beaches, the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, the Essex Scottish, and the Fusiliers Mont-Royal landed below fortified German positions, trapped on open shingle with little cover. The approach became, in survivors’ words, a “shooting gallery.” The 14th Army Tank Regiment (Calgary Regiment) launched 27 Churchill tanks in support of the infantry. Only 15 reached the seawall; beyond it, anti-tank obstacles blocked entry into the town. Forced back, the tanks provided covering fire for the infantry before being destroyed or abandoned on the beach. None returned; all crews were killed or captured. Casualties were staggering: 916 Canadians killed, 1,946 taken prisoner: 3,367 in all. While Dieppe’s costly lessons helped to shape Allied planning for D-Day, debate continues over whether the lessons-learned justified the human price paid that day.

This image, taken by a German military photographer after the battle, is both propaganda and record. The bodies of two fallen soldiers were deliberately positioned on the shingle for effect, the rear one believed by some to be a U.S. Ranger, underscoring German claims of total Allied defeat. Behind them, a Churchill tank lies immobilized, its tracks sunk into loose pebbles. To the right, a landing craft burns, smoke curling skyward. Beneath the staging, however, the tragedy is real. These men died here, alongside hundreds of others, in one of Canada’s bloodiest single days of the war. The wreckage—armour, landing craft, and human life—captures both the human cost of Dieppe and the way its meaning was manipulated: a failed raid turned into a symbol, its lessons written in blood, its consequences carried forward to the Allied return to France on 6 June 1944.

Explore Further:

Juno Beach Centre – Dieppe RaidVeterans Affairs Canada – The Dieppe RaidDepartment of National Defence – Preliminary Report on Dieppe

Claude P. Dettloff / Vancouver Daily Province / City of Vancouver

Archives, AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-3338. Public domain.

Archives, AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-3338. Public domain.

On 1 October 1940, photographer Claude Dettloff captured this moment on the streets of New Westminster, British Columbia, as soldiers of the British Columbia Regiment (Duke of Connaught’s Own Rifles) marched toward a waiting train. Among them was Private Jack Bernard, seen in the frame, as his five-year-old son, Warren “Whitey” Bernard, breaks free from his mother’s grasp and reaches for his father’s outstretched hand. Published the next day, the photograph quickly became one of Canada’s most iconic wartime images. Reproduced internationally and used in Victory Bond campaigns, it came to symbolize the experience of thousands of Canadian families separated by war. In the autumn of 1940, Canada had been at war for just over a year, yet uncertainty hung over every farewell. Families did not know how long separations would last, or who among their loved ones might not return.

Image Description: In the foreground, young Warren Bernard reaches toward his father, his small hand outstretched, his expression urgent and unguarded. Beside him, Bernice Bernard leans instinctively forward, her hand extended to steady him as the column of soldiers marches past, rifles slung and eyes fixed ahead. Private Jack Bernard turns his head toward his son, a loving acknowledgment in the midst of duty. Solemnly facing the camera on the left of the photograph, behind Bernice Bernard is Agnes Confortin (née Power), whose brother Wilfred Power was killed near Arnhem, Netherlands in March 1945.

The photograph’s quiet power lies in its universality. Though it captures one street, one family, and one moment in time, it reflects a shared reality for countless Canadians during the war: children reaching for parents they would not see for years, families suspended between ordinary life and a world transformed by conflict. It stands as both a personal memory and a collective symbol of longing, worry, love, and endurance.

Image Description: In the foreground, young Warren Bernard reaches toward his father, his small hand outstretched, his expression urgent and unguarded. Beside him, Bernice Bernard leans instinctively forward, her hand extended to steady him as the column of soldiers marches past, rifles slung and eyes fixed ahead. Private Jack Bernard turns his head toward his son, a loving acknowledgment in the midst of duty. Solemnly facing the camera on the left of the photograph, behind Bernice Bernard is Agnes Confortin (née Power), whose brother Wilfred Power was killed near Arnhem, Netherlands in March 1945.

The photograph’s quiet power lies in its universality. Though it captures one street, one family, and one moment in time, it reflects a shared reality for countless Canadians during the war: children reaching for parents they would not see for years, families suspended between ordinary life and a world transformed by conflict. It stands as both a personal memory and a collective symbol of longing, worry, love, and endurance.

Explore Further:

Democracy at War – Life on the Home FrontVeterans Affairs Canada – Women on the Home FrontVeterans Affairs Canada – Wait for Me Daddy SculptureCity of Vancouver Archives – Original Photograph Record

Gilbert Alexander Milne. Library and Archives Canada /PA-

122765

122765

On 6 June 1944, Allied forces launched Operation Overlord, the largest seaborne invasion in history, to breach the Atlantic Wall and begin the liberation of Western Europe. Alongside British troops at Sword and Gold Beaches and American forces at Omaha and Utah beaches, more than 14,000 Canadians of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade came ashore on Juno Beach. Canadian paratroops dropped behind the enemy lines. Meanwhile, Canadians in the Royal Canadian Navy and Royal Canadian Air Force provided transport and bombardment. The immediate objectives were to open beach exits, silence strongpoints, and push inland. Conditions were brutal. High winds and offshore sandbars forced many craft to drop troops far from shore, leaving men to wade through chest-deep water under machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire. Bunkers, mines, and interlocking fields of fire cut down the first waves, yet by midday Canadians had broken through and secured a foothold. The cost was steep: 359 Canadians killed on 6 June, with total Canadian casualties that day exceeding 1,000; over the next ten weeks, more than 5,000 Canadians would die in the Normandy campaign.

For Canadians, Juno came to embody sacrifice and achievement. The tragedy of Dieppe two years earlier had never reflected a lack of courage; it underscored the limits of planning and resources. At Juno, that same resolve—now coupled with improved preparation and support—helped carry the day. In this picture , troops of the Stormont, Dundas & Glengarry (SD&G) Highlanders wade ashore from LCI(L) 299 on the Nan White sector of Juno Beach near Bernières-sur-Mer. Men steady themselves on ropes, rifles, kit, and even bicycles held high. Just above the seawall, a Sherman “DD” tank prepares to move out; nearby, anti-aircraft crews set up to shield the fragile foothold. In the distance, shattered houses mark the violence of the morning’s fight. By around 12:30 p.m., the SD&G were fully ashore, but congestion and jubilant civilians slowed their progress off the beach. They finally moved out at 4:55 p.m., reached Bény-sur-Mer by 6:30 p.m., and were ordered to hold at dusk, taking mortar fire as they dug in. One man was killed and thirteen wounded, a stark reminder that even after the beaches were won, the risks were not over.

For Canadians, Juno came to embody sacrifice and achievement. The tragedy of Dieppe two years earlier had never reflected a lack of courage; it underscored the limits of planning and resources. At Juno, that same resolve—now coupled with improved preparation and support—helped carry the day. In this picture , troops of the Stormont, Dundas & Glengarry (SD&G) Highlanders wade ashore from LCI(L) 299 on the Nan White sector of Juno Beach near Bernières-sur-Mer. Men steady themselves on ropes, rifles, kit, and even bicycles held high. Just above the seawall, a Sherman “DD” tank prepares to move out; nearby, anti-aircraft crews set up to shield the fragile foothold. In the distance, shattered houses mark the violence of the morning’s fight. By around 12:30 p.m., the SD&G were fully ashore, but congestion and jubilant civilians slowed their progress off the beach. They finally moved out at 4:55 p.m., reached Bény-sur-Mer by 6:30 p.m., and were ordered to hold at dusk, taking mortar fire as they dug in. One man was killed and thirteen wounded, a stark reminder that even after the beaches were won, the risks were not over.

Explore Further:

Juno Beach Centre – D-Day OverviewCanadian War Museum – The Battle of NormandyJuno Beach Centre – SD&G on D-Day

Sydney Post-Record, 17 October 1942. Permission from Postmedia on behalf of PNI Maritimes.

In the first years of the war, the Gulf of St. Lawrence,Cabot Strait, and Halifax approaches became hunting grounds for U-boats along lightly defended routes. In the early hours of 14 October 1942, the German submarine U-69 torpedoed and sank the civilian ferry SS Caribou in the Cabot Strait between Sydney, Nova Scotia, and Port aux Basques, Newfoundland. Of the 237 people aboard, 137 were killed, including 46 crew, 57 military personnel, and 34 civilians. Survivors were picked up by the convoy escort HMCS Grandmère. Among the dead were women, children, and entire families travelling between Newfoundland and the mainland. The sinking shocked Canada and was among the deadliest attacks on civilians in Canadian waters of the war.

Canada’s navy would grow into the fourth largest in the world by war’s end, but in 1942 its escort fleet was small, anti-submarine technology limited, and patrol lines stretched thin. For many Canadians, the Caribou was a turning point: the Atlantic war, once distant, had arrived at home. Newspapers seized on the story even as wartime censorship limited details; headlines stressed morale and urgency. Public support galvanized around stronger coastal defences, tighter convoy procedures, and more escort vessels. Despite this response, the sinking left lasting scars in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia communities where entire families were lost. This front page of the Sydney Post-Record, published 17 October 1942, captures the immediate shock of the sinking. A bold headline dominates the page, declaring the “Caribou Tragedy” in urgent type, leaving no doubt about the scale of loss. Sub-headlines, including “Caribou Sunk by Nazi U-Boat Off St. Paul’s Island” and “Torpedoing of Caribou Brings War to Canada,” frame the attack as both a personal tragedy and a national crisis. A photograph of the ferry accompanies statements from the Navy Minister, underscoring the government’s effort to control the narrative while rallying public resolve. For readers in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, the impact was visceral: familiar names filled the casualty lists, and familiar waters had become a battlefield.

Canada’s navy would grow into the fourth largest in the world by war’s end, but in 1942 its escort fleet was small, anti-submarine technology limited, and patrol lines stretched thin. For many Canadians, the Caribou was a turning point: the Atlantic war, once distant, had arrived at home. Newspapers seized on the story even as wartime censorship limited details; headlines stressed morale and urgency. Public support galvanized around stronger coastal defences, tighter convoy procedures, and more escort vessels. Despite this response, the sinking left lasting scars in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia communities where entire families were lost. This front page of the Sydney Post-Record, published 17 October 1942, captures the immediate shock of the sinking. A bold headline dominates the page, declaring the “Caribou Tragedy” in urgent type, leaving no doubt about the scale of loss. Sub-headlines, including “Caribou Sunk by Nazi U-Boat Off St. Paul’s Island” and “Torpedoing of Caribou Brings War to Canada,” frame the attack as both a personal tragedy and a national crisis. A photograph of the ferry accompanies statements from the Navy Minister, underscoring the government’s effort to control the narrative while rallying public resolve. For readers in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, the impact was visceral: familiar names filled the casualty lists, and familiar waters had become a battlefield.

Explore Further:

Juno Beach Centre – Submarines Attack in the St. LawrenceHeritage Newfoundland and Labrador – Sinking of the CaribouVeterans Affairs Canada - The Battle of the Gulf of St. Lawrence

Department of National Defence Image PL-144281. Public

domain

domain

By 1943, the strategic bombing campaign over Europe had become one of the most dangerous and demanding operations of the war, and Canadians served at its heart. More than 50,000 Canadians served in Bomber Command, most in No. 6 Group RCAF, formed in 1943. Night after night, Canadians crews flew deep into Germany, over cities, industrial centres, and defended heartlands. These were battles fought in darkness, against Germany’s integrated air defences: radar-controlled searchlights, anti-aircraft batteries, and prowling night-fighter wings. The odds were brutal: 10,000 Canadians were killed. At points, fewer than half of crews completed a thirty-mission tour, making Bomber Command one of Canada’s deadliest wartime roles.

On 25 April 1945, Bomber Command mounted its last major raid of the war. A combined force of 482 aircraft struck Wangerooge, one of Germany’s Frisian Islands. The target was its coastal batteries guarding access to Bremen and Wilhelmshaven. Tragedy struck when one bomber hit another’s slipstream, triggering a chain reaction that sent six Lancasters into the sea—four Canadian. Another was brought down by anti-aircraft fire. On the ground, more than 120 forced labourers, many Allied POWs, were killed. It came just two weeks before Germany’s surrender. Historians have since debated Bomber Command’s strategy—its objectives, civilian impact, and cost to crews—debates that continue to shape its legacy. Two Lancaster bombers appear in this photograph, one flying low beneath the other, only a few hundred metres apart. Below, Wangerooge’s shoreline is scarred by craters and smoke, fires rippling inland. The geometry of the aircraft contrasts with the chaos below: shattered buildings, billowing smoke, scorched terrain marking the violence of the raid. The photo shows the precision and coordination of the strategic bombing campaign. It also speaks to the human cost for crews facing darkness, cold, and mortal danger, and to the lives lost below. For Canadians, this final mission stands as a testament to endurance, courage, and sacrifice.

On 25 April 1945, Bomber Command mounted its last major raid of the war. A combined force of 482 aircraft struck Wangerooge, one of Germany’s Frisian Islands. The target was its coastal batteries guarding access to Bremen and Wilhelmshaven. Tragedy struck when one bomber hit another’s slipstream, triggering a chain reaction that sent six Lancasters into the sea—four Canadian. Another was brought down by anti-aircraft fire. On the ground, more than 120 forced labourers, many Allied POWs, were killed. It came just two weeks before Germany’s surrender. Historians have since debated Bomber Command’s strategy—its objectives, civilian impact, and cost to crews—debates that continue to shape its legacy. Two Lancaster bombers appear in this photograph, one flying low beneath the other, only a few hundred metres apart. Below, Wangerooge’s shoreline is scarred by craters and smoke, fires rippling inland. The geometry of the aircraft contrasts with the chaos below: shattered buildings, billowing smoke, scorched terrain marking the violence of the raid. The photo shows the precision and coordination of the strategic bombing campaign. It also speaks to the human cost for crews facing darkness, cold, and mortal danger, and to the lives lost below. For Canadians, this final mission stands as a testament to endurance, courage, and sacrifice.

Explore Further:

Juno Beach Centre – RCAF Bomber Squadrons OverseasThe Crucible of War 1939-1945: The Official History of the RCAFBomber Command Museum – 6 Group’s Last Mission

Canadian War Museum, 19710261-1042.

Throughout the Second World War, Canada’s Merchant Navy was a lifeline, carrying food, fuel, munitions, and troops across the Atlantic. Every Allied campaign—from North Africa to D-Day—depended on these supply lines. Crews drawn from fishing villages, prairie towns, and industrial centres sailed storm-lashed routes under constant threat from German U-boats determined to sever that connection. The danger was relentless. Merchant mariners lacked the armour and weaponry of naval escorts, making them vulnerable to torpedoes, mines, and air attacks. When a ship went down, survival often depended on luck, endurance, and fragile Carley floats, small life rafts tossed into freezing seas, hundreds of kilometres from shore. Of the roughly 12,000 Canadians who served, over 1,600 were lost, one of the highest proportional casualty rates of any Canadian service.

The painting reflects this peril but also speaks to resilience. Its creator, Harold Beament (1898–1984), served as both a naval officer and an official war artist attached to the Royal Canadian Navy from 1943 to 1947. Beament’s first-hand knowledge shaped his work: he understood the sea’s danger and the fragile margin between survival and loss. “It was difficult,” he later recalled, “to separate the naval officer from the war artist … I’d be very pleased with the canvas when I went to bed. I’d wake up in the morning and think, ‘I wouldn’t put to sea in that vessel,’ and then I’d start making it seaworthy.” Merchant Navy veterans struggled for recognition, finally gaining full benefits in 1992. Today, their service is remembered as central to Allied victory, and their sacrifices honoured as essential to sustaining the war effort.

In Passing?, survivors drift in a small Carley float, their craft pitched on the heaving Atlantic. One man waves a white flag toward the faint outline of a distant ship, signaling desperately for rescue. Around him, his comrades wait in silence, framed by soft blues and greys that echo the vast, indifferent sea. The title’s question mark captures the moment’s uncertainty: will they be seen, or left to vanish into the waves? Beament transforms a single scene into a universal story of endurance, vulnerability, and hope against overwhelming odds

The painting reflects this peril but also speaks to resilience. Its creator, Harold Beament (1898–1984), served as both a naval officer and an official war artist attached to the Royal Canadian Navy from 1943 to 1947. Beament’s first-hand knowledge shaped his work: he understood the sea’s danger and the fragile margin between survival and loss. “It was difficult,” he later recalled, “to separate the naval officer from the war artist … I’d be very pleased with the canvas when I went to bed. I’d wake up in the morning and think, ‘I wouldn’t put to sea in that vessel,’ and then I’d start making it seaworthy.” Merchant Navy veterans struggled for recognition, finally gaining full benefits in 1992. Today, their service is remembered as central to Allied victory, and their sacrifices honoured as essential to sustaining the war effort.

In Passing?, survivors drift in a small Carley float, their craft pitched on the heaving Atlantic. One man waves a white flag toward the faint outline of a distant ship, signaling desperately for rescue. Around him, his comrades wait in silence, framed by soft blues and greys that echo the vast, indifferent sea. The title’s question mark captures the moment’s uncertainty: will they be seen, or left to vanish into the waves? Beament transforms a single scene into a universal story of endurance, vulnerability, and hope against overwhelming odds

Explore Further:

Department of National Defence – The Merchant NavyVeterans Affairs Canada – The Merchant NavyDepartment of National Defence – War Art

Canadian War Museum, CWM 19920085-1104 No.1 PR452.

Historical Context: On Christmas Day 1941, Hong Kong fell after a determined 17-day defence. Nearly 2,000 Canadians of the Royal Rifles of Canada and the Winnipeg Grenadiers had arrived only weeks earlier as part of “C Force,” in a convoy escorted by HMCS Prince Robert. Their stand came amid a broader Japanese offensive launched across the Pacific, including the attack on Pearl Harbor. Surrounded and outnumbered, the garrison surrendered after heavy losses: 290 Canadians killed and 493 wounded. The survivors faced nearly four years of captivity, enduring forced labour, starvation, disease, and cruelty in camps such as Sham Shui Po. Beginning in 1943, Canadians were transported to prison camps across Japan—Niigata, Narumi, Yoshima, Ōmine and others—where they laboured in mines, docks, and factories in severe cold on meager rations, sometimes as low as 800 calories a day. By April 1944, only about 220 members of ‘C Force’ remained in Hong Kong, largely officers and the seriously ill. A deadly diphtheria outbreak in 1942 and malnutrition claimed 264 more lives, bringing the total Canadian death toll linked to Hong Kong to more than 550.

In August 1945, HMCS Prince Robert returned to Hong Kong with the Allied liberation force. Its landing party secured Sham Shui Po and began evacuations, including men the ship had helped bring to war nearly four years earlier. On 16 September, Prince Robert’s captain represented Canada at the formal Japanese surrender of Hong Kong. The ship returned to Esquimalt, B.C., on 20 October 1945, carrying repatriated Canadians.

In this image newly freed servicemen, mostly Canadian with British comrades, stand shirtless in Hong Kong’s heat. Ribs and shoulders show years of hunger; one man balances on crutches, another wears only a simple loincloth, reflecting the scarcity of captivity. Some clutch cigarettes; glances are subdued. A few attempt small smiles, but their faces carry relief, disbelief, and exhaustion. As one Royal Rifles prisoner recalled, “Those were days of jubilation in Sham Shui Po!” Worn shorts, improvised sandals, and mismatched boots speak to the hand-to-mouth existence of camp life. Behind them, stacked crates and a rough concrete edge mark the camp’s outskirts; no longer a cage, but not yet home. Their subtle lean toward the camera suggests forward motion, the fragile dignity of men who endured forty-four months of deprivation and are, at last, being seen.

In August 1945, HMCS Prince Robert returned to Hong Kong with the Allied liberation force. Its landing party secured Sham Shui Po and began evacuations, including men the ship had helped bring to war nearly four years earlier. On 16 September, Prince Robert’s captain represented Canada at the formal Japanese surrender of Hong Kong. The ship returned to Esquimalt, B.C., on 20 October 1945, carrying repatriated Canadians.

In this image newly freed servicemen, mostly Canadian with British comrades, stand shirtless in Hong Kong’s heat. Ribs and shoulders show years of hunger; one man balances on crutches, another wears only a simple loincloth, reflecting the scarcity of captivity. Some clutch cigarettes; glances are subdued. A few attempt small smiles, but their faces carry relief, disbelief, and exhaustion. As one Royal Rifles prisoner recalled, “Those were days of jubilation in Sham Shui Po!” Worn shorts, improvised sandals, and mismatched boots speak to the hand-to-mouth existence of camp life. Behind them, stacked crates and a rough concrete edge mark the camp’s outskirts; no longer a cage, but not yet home. Their subtle lean toward the camera suggests forward motion, the fragile dignity of men who endured forty-four months of deprivation and are, at last, being seen.

Explore Further:

Veterans Affairs Canada – Canadians in Hong KongVeterans Affairs Canada – Prisoners of War in the Second World WarCommonwealth War Graves Commission – Sai Wan War Cemetery

Library and Archives Canada / PA-141388.

By October 1943, Canadian forces were advancing through the rugged hills of southern Italy as part of the Allied campaign up the peninsula. Fighting was fierce, and losses came not only from direct contact but also from mines, shelling, and ambushes hidden in the terrain. As towns and ridges changed hands, soldiers often paused between operations to recover and care for their wounded, bury their dead, and prepare for the next push forward.

By the Second World War, battlefield burials were carried out under formal Graves Registration procedures, but the first markers were often improvised in the field: rough wooden crosses placed close to where the fallen had died, later replaced by permanent headstones under the care of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). These practices reflected a shift in wartime commemoration: the promise that every name would be recorded, every grave respected, and no one left without recognition. In this photograph, taken at Baranello, we see a moment where movement and remembrance intersect. Even as operations continued, Canadian soldiers paused to prepare markers for their comrades, creating small, temporary acts of dignity that would carry forward into lasting commemoration.

Pictured here; Corporal W. F. Blackwood and Private R. J. Barnes of the Seaforth Highlanders’ Pioneer Platoon work with quiet concentration outside a stone building in Baranello, Italy, on 19 October 1943. At a rough wooden table, they paint and letter grave markers for their fallen comrades. One soldier leans over a cross, freehanding names in dark paint; beside him, a list guides each inscription, ensuring every name matches the record. Finished markers lean against the wall, drying in the sunlight. Painted white with black lettering, they follow a simple wartime format: the regiment’s name at the top, the soldier’s details carefully lettered below, and a panel recording the date of death. These crosses were never meant to last, they marked the place and the promise, bridging the immediate need for dignity in the field with the permanent care that would come later under the CWGC. The photograph captures more than routine procedure. It shows an act of service within the broader campaign: pausing to name, honour, and remember the dead even as the war pressed on. Here, the living record the names of the fallen, carrying them forward into ordered cemeteries and enduring memory.

By the Second World War, battlefield burials were carried out under formal Graves Registration procedures, but the first markers were often improvised in the field: rough wooden crosses placed close to where the fallen had died, later replaced by permanent headstones under the care of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). These practices reflected a shift in wartime commemoration: the promise that every name would be recorded, every grave respected, and no one left without recognition. In this photograph, taken at Baranello, we see a moment where movement and remembrance intersect. Even as operations continued, Canadian soldiers paused to prepare markers for their comrades, creating small, temporary acts of dignity that would carry forward into lasting commemoration.

Pictured here; Corporal W. F. Blackwood and Private R. J. Barnes of the Seaforth Highlanders’ Pioneer Platoon work with quiet concentration outside a stone building in Baranello, Italy, on 19 October 1943. At a rough wooden table, they paint and letter grave markers for their fallen comrades. One soldier leans over a cross, freehanding names in dark paint; beside him, a list guides each inscription, ensuring every name matches the record. Finished markers lean against the wall, drying in the sunlight. Painted white with black lettering, they follow a simple wartime format: the regiment’s name at the top, the soldier’s details carefully lettered below, and a panel recording the date of death. These crosses were never meant to last, they marked the place and the promise, bridging the immediate need for dignity in the field with the permanent care that would come later under the CWGC. The photograph captures more than routine procedure. It shows an act of service within the broader campaign: pausing to name, honour, and remember the dead even as the war pressed on. Here, the living record the names of the fallen, carrying them forward into ordered cemeteries and enduring memory.

Explore Further:

Democracy at War – The Sicilian and Italian Campaigns, 1943-1945Veterans Affairs Canada – Canada – Italy, 1943-1945Veterans Affairs Canada – The Italian CampaignCWGC – Moro River Canadian War Cemetery

Harold G. Aikman / Department of National Defence / Library and

Archives Canada / PA-133244. Public domain.

Archives Canada / PA-133244. Public domain.

July 1944, Canadian forces were fighting some of the most intense battles of the Normandy campaign. After landing on Juno Beach on D-Day, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and supporting armour pushed toward Caen, confronting entrenched German resistance in the bocage’s narrow lanes and hedgerows. After Operation Charnwood (8–9 July) saw the capture of northern Caen, the southern half of the city and the commanding Verrières Ridge remained in German hands. Preparing for Operation Atlantic (18–21 July), Canadians endured constant shelling, sniper fire, and counterattacks. By mid-July, Canadian formations had suffered heavily, part of the more than 18,000 Canadians casualties during the campaign.

In this environment, Regimental Aid Posts (RAPs) formed the first link in the chain of survival. Positioned just behind the front, they were staffed by battalion medical officers, stretcher-bearers, and orderlies who stabilized casualties under fire before evacuation to field ambulances and casualty clearing stations further to the rear. These small posts were often improvised in farmhouses, barns, or roadside ditches, anywhere shelter could be found within reach of the fighting. Shown here, a wounded Canadian soldier lies on the ground, his head wrapped in a white bandage. Beside him, his dented helmet marks the narrow margin between life and death. Two men work intently over him: a medic and Chaplain John W. Forth, his clerical collar visible beneath his battledress. Wearing a Red Cross armband, Forth steadies the soldier as the medic dresses the wound. Earlier the same day, Forth led Holy Communion in a nearby orchard; hours later, he is at the aid post, helping stabilize the wounded, a reminder that chaplains’ duties often extended far beyond prayer into direct, urgent care.

Nearby, another soldier opens medical supplies while, at the frame’s edge, a fourth soldier watches the hedgerow for enemy movement. Around them, churned earth, discarded kit, and the close press of Normandy’s bocage suggest chaos just beyond the frame. The photograph captures a fleeting act of care amid relentless battle: comrades protecting and caring for their wounded mate and the rituals of survival at the edge of combat.

In this environment, Regimental Aid Posts (RAPs) formed the first link in the chain of survival. Positioned just behind the front, they were staffed by battalion medical officers, stretcher-bearers, and orderlies who stabilized casualties under fire before evacuation to field ambulances and casualty clearing stations further to the rear. These small posts were often improvised in farmhouses, barns, or roadside ditches, anywhere shelter could be found within reach of the fighting. Shown here, a wounded Canadian soldier lies on the ground, his head wrapped in a white bandage. Beside him, his dented helmet marks the narrow margin between life and death. Two men work intently over him: a medic and Chaplain John W. Forth, his clerical collar visible beneath his battledress. Wearing a Red Cross armband, Forth steadies the soldier as the medic dresses the wound. Earlier the same day, Forth led Holy Communion in a nearby orchard; hours later, he is at the aid post, helping stabilize the wounded, a reminder that chaplains’ duties often extended far beyond prayer into direct, urgent care.

Nearby, another soldier opens medical supplies while, at the frame’s edge, a fourth soldier watches the hedgerow for enemy movement. Around them, churned earth, discarded kit, and the close press of Normandy’s bocage suggest chaos just beyond the frame. The photograph captures a fleeting act of care amid relentless battle: comrades protecting and caring for their wounded mate and the rituals of survival at the edge of combat.