First World War

The First World War (1914–1918) was Canada’s first experience of total war. It was a conflict fought not only on land, sea, and in the air, but also in households, factories, shipyards, and fields across the country. More than 650,000 Canadians served, nearly one in ten of the population. From the mud of Flanders to the waters of the Atlantic and the skies above Europe, Canadian forces earned a reputation for determination and skill in battles such as the Second Battle of Ypres (1915), the Somme (1916), Vimy Ridge (1917), Passchendaele (1917), and the Hundred Days Campaign (1918).

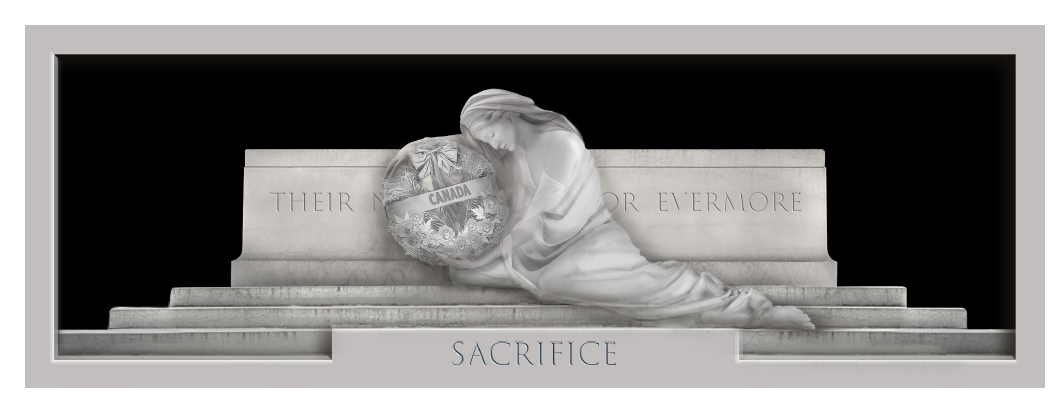

At home, the strain of war deepened existing divisions. In 1917, Parliament passed the Military Service Act, introducing conscription to replace battlefield losses, widening the rift between English- and French-speaking Canadians. Women stepped into new roles, working long hours in munitions plants, running farms, and packing relief parcels. That same year, the Wartime Elections Act and Military Voters Act extended the federal vote to military personnel and, for the first time, to some women—a turning point in Canadian political life. The cost was immense: more than 66,000 dead and 172,000 wounded. Many of the injured endured life-altering physical disabilities, while others carried invisible psychological wounds from years of brutal combat. Nearly every community was touched by grief: empty chairs at dinner tables, names carved into local memorials, families changed forever. The war redefined “heroism,” expanding it beyond the victorious soldier to include the endurance of the wounded, the perseverance of families, and the resilience of those who carried on. Canadian expressions like In Flanders Fields gave voice to these losses, becoming symbols of remembrance worldwide.

This column honours the more than 66,000 Canadians who died in the First World War, including the 61,672 names recorded in the First World War Book of Remembrance and the 2,403 listed in the Newfoundland Book of Remembrance, both housed in the Peace Tower’s Memorial Chamber in Ottawa.

External Links:

Newfoundland Book of Remembrance

At home, the strain of war deepened existing divisions. In 1917, Parliament passed the Military Service Act, introducing conscription to replace battlefield losses, widening the rift between English- and French-speaking Canadians. Women stepped into new roles, working long hours in munitions plants, running farms, and packing relief parcels. That same year, the Wartime Elections Act and Military Voters Act extended the federal vote to military personnel and, for the first time, to some women—a turning point in Canadian political life. The cost was immense: more than 66,000 dead and 172,000 wounded. Many of the injured endured life-altering physical disabilities, while others carried invisible psychological wounds from years of brutal combat. Nearly every community was touched by grief: empty chairs at dinner tables, names carved into local memorials, families changed forever. The war redefined “heroism,” expanding it beyond the victorious soldier to include the endurance of the wounded, the perseverance of families, and the resilience of those who carried on. Canadian expressions like In Flanders Fields gave voice to these losses, becoming symbols of remembrance worldwide.

This column honours the more than 66,000 Canadians who died in the First World War, including the 61,672 names recorded in the First World War Book of Remembrance and the 2,403 listed in the Newfoundland Book of Remembrance, both housed in the Peace Tower’s Memorial Chamber in Ottawa.

External Links:

Newfoundland Book of Remembrance

Explore Links:

First World War Book of RemembranceNewfoundland Book of Remembrance

Imperial War Museum, Q 863 - Photographer unknown, 1916

The First World War saw aviation evolve from an improvised reconnaissance tool to a critical arm of modern warfare. In 1914, aircraft were slow, unarmed, and fragile, barely powerful enough to carry their own pilot aloft. By 1918, they included powerful fighters, fixed-wing heavy bombers, and specialized ground- attack craft. Alongside this technological leap came new strategies—coordinated bombing, fighter escorts, and aerial interdiction—many of which later shaped the Second World War’s air campaigns.

More than 20,000 Canadians served with distinction in the British Royal Flying Corps, Royal Naval Air Service, and later the Royal Air Force. They gathered vital intelligence, escorted reconnaissance flights, attacked enemy positions, and contested control of the skies. Nearly 1,400 Canadians were killed in the air services. While Canada’s own air units would not be formed until after the war, the experience of these pilots and observers laid the foundation for the postwar Canadian Air Force (1920) and the Royal Canadian Air Force (1924), fundamentally shaping the nation’s future in military aviation.

This photograph, taken during the Battle of the Somme in 1916, shows soldiers gathered around the wreckage of a British biplane that crash-landed near Canadian trenches outside Pozières. Its fabric skin is torn, the wings and struts splintered, and the pilot missing from the frame. The scene captures the ever- present dangers faced by airmen: mechanical failure, unpredictable weather, anti-aircraft fire, and aerial combat. Its proximity to Canadian trenches underscores the thin divide between the air and ground war, and the shared perils that linked them. It is a reminder that for airmen, as for infantry, survival often hinged on skill, luck, and the resilience of those ready to help when disaster struck.

More than 20,000 Canadians served with distinction in the British Royal Flying Corps, Royal Naval Air Service, and later the Royal Air Force. They gathered vital intelligence, escorted reconnaissance flights, attacked enemy positions, and contested control of the skies. Nearly 1,400 Canadians were killed in the air services. While Canada’s own air units would not be formed until after the war, the experience of these pilots and observers laid the foundation for the postwar Canadian Air Force (1920) and the Royal Canadian Air Force (1924), fundamentally shaping the nation’s future in military aviation.

This photograph, taken during the Battle of the Somme in 1916, shows soldiers gathered around the wreckage of a British biplane that crash-landed near Canadian trenches outside Pozières. Its fabric skin is torn, the wings and struts splintered, and the pilot missing from the frame. The scene captures the ever- present dangers faced by airmen: mechanical failure, unpredictable weather, anti-aircraft fire, and aerial combat. Its proximity to Canadian trenches underscores the thin divide between the air and ground war, and the shared perils that linked them. It is a reminder that for airmen, as for infantry, survival often hinged on skill, luck, and the resilience of those ready to help when disaster struck.

Explore Further:

Canadian War Museum – Canada and the Air WarDepartment of History and Heritage – First World War Air WarCanadian Airmen and the First World War - Monograph

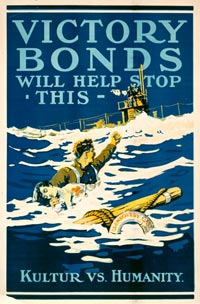

Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1983-28-872. From a Canadian Victory Bonds poster, 1918.

On the evening of 27 June 1918, the Canadian hospital ship Llandovery Castle, clearly marked with Red Cross symbols, was torpedoed without warning off the coast of Ireland by the German submarine U-86 while sailing from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Liverpool, England. Having delivered recovering soldiers to Canada earlier that month, it was returning to Britain with 258 crew and medical personnel, including 14 Nursing Sisters of the Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC). This voyage was part of the constant movement of people and matériel across the Atlantic that sustained the Allied war effort. The Hague Convention permitted an enemy vessel to stop and search a hospital ship, but never to sink it. U-86 made no attempt to search the Llandovery Castle, which sank in less than ten minutes. Nevertheless, three lifeboats launched and began pulling survivors from the water. U-86 surfaced and interrogated the survivors, seeking proof of munitions aboard the hospital ship. Finding none, the submarine’s crew opened fire on the lifeboats in an attempt to kill all witnesses to the crime. Thirty-six hours later, HMS Lysander found a sole remaining lifeboat adrift with 24 survivors, including six men from the CAMC. All 14 Nursing Sisters had been killed, dragged under as the ship went down. The loss was the deadliest Canadian naval disaster of the war and a flagrant violation of international law protecting hospital ships. News of the attack and of the nursing sisters’ fate intensified anti-German sentiment in Canada and became a centrepiece of Allied propaganda to rally public support. It also underscored the vulnerability of non-combatants in total war, where even protected vessels could be deliberately targeted. This Victory Bonds poster depicts victims of the Llandovery Castle tragedy struggling in the Atlantic Ocean, a nurse’s body clutched by a drowning soldier. Behind them, the surfaced German U-boat looms over the scene, its crew visible. The bold text: “Victory Bonds Will Help Stop This” , frames the sinking as a moral battle, while the tagline “Kultur vs. Humanity” pits German militarism against Allied values. The composition is dramatic, harnessing grief and outrage to mobilize Canadians to invest in the war effort. Beneath its stylized urgency lies a grim truth: among the 234 dead were 14 Canadian Nursing Sisters, and 70 men of the CAMC, killed in the sinking of a hospital ship, an act remembered as one of the war’s most notorious atrocities.

Explore Further:

Legion Magazine – Criminal IntentCEFRG – Sinking of Llandovery Castle in the Great War (1918 Report)

Library and Archives Canada, PA-002165.

By November 1917, the Third Battle of Ypres, known to Canadians as the Battle of Passchendaele, had become synonymous with endurance and sacrifice. Months of shelling and relentless autumn rains had transformed the landscape into a quagmire of flooded craters and churned mud. When the Canadians were ordered to capture the shattered village of Passchendaele, Lieutenant-General Arthur Currie, commanding the Canadian Corps, warned it would cost at least 16,000 casualties. His estimate nearly correct: in just over two weeks of fighting, Canadians suffered more than 15,600 killed, wounded, or missing.

The scale of the battle was matched by its misery. Advancing even a few metres required hauling supplies and wounded comrades through knee-deep muck under continuous artillery fire. Wounded men often drowned where they fell. Amid this devastation, to surrender was fraught with danger. In the chaos of combat, prisoners were sometimes shot or killed accidentally, and routes of retreat were often under bombardment. Yet when surrender was accepted, German and Canadian prisoners alike were marched to the rear where they faced long, uncertain journeys to camps, inadequate food, and exposure to disease. Canadians captured at least 42,000 German soldiers during the war, including hundreds at Passchendaele. Conversely, about 3,800 Canadians were taken prisoner, many spending months or years in harsh German camps. While treatment varied, most POWs survived to be repatriated after the Armistice, testament to a fragile but enduring respect for the laws of war.

Pictured here, a Canadian soldier leans across the churned mud of Passchendaele to light a cigarette for a captured German. Both are surrounded by a desolate expanse scarred by shellfire. It is a quiet, fleeting exchange in a battle otherwise marked by unrelenting violence. Acts of humanity like this were uncommon under fire but not unheard of. Immediately after accepting surrender, soldiers sometimes offered water, shared cigarettes, or tended to wounds, small gestures of dignity that briefly cut through the dehumanization of trench warfare. Here, in the midst of unimaginable suffering, two young men from opposing armies meet briefly as fellow human beings. The image endures as a reminder that even amid devastation, compassion persisted.

The scale of the battle was matched by its misery. Advancing even a few metres required hauling supplies and wounded comrades through knee-deep muck under continuous artillery fire. Wounded men often drowned where they fell. Amid this devastation, to surrender was fraught with danger. In the chaos of combat, prisoners were sometimes shot or killed accidentally, and routes of retreat were often under bombardment. Yet when surrender was accepted, German and Canadian prisoners alike were marched to the rear where they faced long, uncertain journeys to camps, inadequate food, and exposure to disease. Canadians captured at least 42,000 German soldiers during the war, including hundreds at Passchendaele. Conversely, about 3,800 Canadians were taken prisoner, many spending months or years in harsh German camps. While treatment varied, most POWs survived to be repatriated after the Armistice, testament to a fragile but enduring respect for the laws of war.

Pictured here, a Canadian soldier leans across the churned mud of Passchendaele to light a cigarette for a captured German. Both are surrounded by a desolate expanse scarred by shellfire. It is a quiet, fleeting exchange in a battle otherwise marked by unrelenting violence. Acts of humanity like this were uncommon under fire but not unheard of. Immediately after accepting surrender, soldiers sometimes offered water, shared cigarettes, or tended to wounds, small gestures of dignity that briefly cut through the dehumanization of trench warfare. Here, in the midst of unimaginable suffering, two young men from opposing armies meet briefly as fellow human beings. The image endures as a reminder that even amid devastation, compassion persisted.

Explore Further:

Canadian War Museum – PasschendaeleJournal of Military History – The Politics of SurrenderLegion Magazine – Prisoners of War

Canadian War Museum 19710261-0160. William Longstaff, The Ghosts of Vimy Ridge, 1929. Courtesy of Chris Copland.

In 1920, the Canadian Battlefields Memorials Commission was established to oversee the creation of memorials at key Canadian battle sites on the Western Front. Two years later, France granted Canada perpetual use of the land at Vimy Ridge to honour the Canadians who had fought and died there. Following a design competition won by sculptor Walter Allward, construction began in 1924 on the highest point of the ridge. The soaring granite memorial was unveiled in 1936 before a crowd of more than 100,000 people, including 6,000 Canadian veterans who made the pilgrimage from across the country. Allward explained that the design was inspired by a dream in which dead soldiers rose to join the living in battle, a vision that shaped his tribute to what Canada owed its fallen. The monument became both a national shrine and a symbol of Canada’s emergence on the world stage.

Today, Vimy remains the most-visited Canadian battlefield site in Europe, a place where many travelling Canadians stop to honour the fallen. The landscape, pitted with preserved craters and trenches, is still largely off-limits due to the lingering danger of unexploded ordnance. These scars, left undisturbed, ensure the ground itself remains a witness to the battle. From the veterans who gathered in 1936 and after to students and families who walk its paths today, Vimy continues to link generations of Canadians to the memory of sacrifice and service.

Australian-born artist William Longstaff visited the Vimy site and was deeply moved by the memorial and the battlefield’s lingering atmosphere. Already known for works blending battlefield realism with spectral imagery, he painted The Ghosts of Vimy Ridge in 1929, showing rows of translucent soldiers rising from the scarred ground toward Allward’s towering memorial. In echo of Allward’s own vision, Longstaff depicted the fallen as still present, their spectral ranks reflecting the postwar search for meaning in loss. The painting’s night-blue tones and spectral ranks of soldiers give the scene a dreamlike solemnity. The Vimy Memorial glows pale in the distance, its twin pylons rising like guardians over the fallen. Longstaff’s work collapses time: the ghosts march not just toward a monument, but toward recognition,

remembrance, and peace. The living viewer becomes a witness to this silent return, confronted with the scale of sacrifice and the enduring bond between the battlefield and the memory it enshrines.

Today, Vimy remains the most-visited Canadian battlefield site in Europe, a place where many travelling Canadians stop to honour the fallen. The landscape, pitted with preserved craters and trenches, is still largely off-limits due to the lingering danger of unexploded ordnance. These scars, left undisturbed, ensure the ground itself remains a witness to the battle. From the veterans who gathered in 1936 and after to students and families who walk its paths today, Vimy continues to link generations of Canadians to the memory of sacrifice and service.

Australian-born artist William Longstaff visited the Vimy site and was deeply moved by the memorial and the battlefield’s lingering atmosphere. Already known for works blending battlefield realism with spectral imagery, he painted The Ghosts of Vimy Ridge in 1929, showing rows of translucent soldiers rising from the scarred ground toward Allward’s towering memorial. In echo of Allward’s own vision, Longstaff depicted the fallen as still present, their spectral ranks reflecting the postwar search for meaning in loss. The painting’s night-blue tones and spectral ranks of soldiers give the scene a dreamlike solemnity. The Vimy Memorial glows pale in the distance, its twin pylons rising like guardians over the fallen. Longstaff’s work collapses time: the ghosts march not just toward a monument, but toward recognition,

remembrance, and peace. The living viewer becomes a witness to this silent return, confronted with the scale of sacrifice and the enduring bond between the battlefield and the memory it enshrines.

Explore Further:

House of Commons – The Ghosts of Vimy RidgeThe Vimy Foundation – History of Vimy RidgeCanadian Military History – The 1936 Vimy Pilgrimage

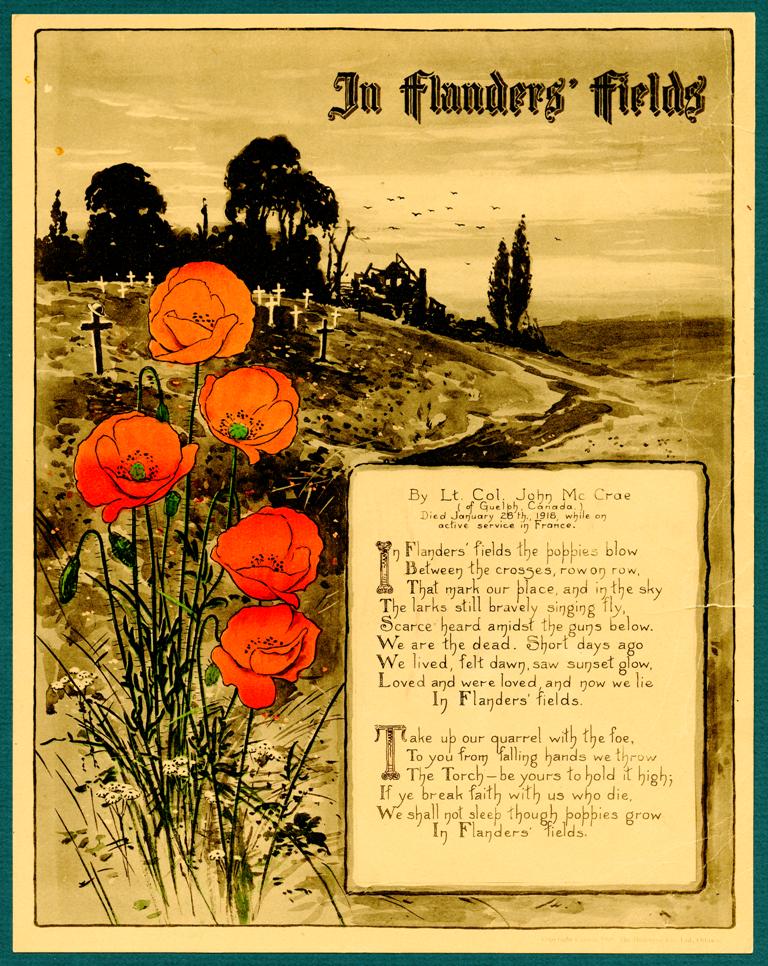

Illustrated version of In Flanders Fields, 1918. Public domain.

Few works of art have shaped remembrance as deeply as In Flanders Fields. Written in May 1915 by Canadian medical officer Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae—who also served in the South African War—the poem emerged from the horrors of the Second Battle of Ypres. In late April 1915, German forces released chlorine gas. Despite being outnumbered, the Canadian Division held its ground at terrible cost: more than 6,000 casualties in just over two weeks. Among the dead was Lieutenant Alexis Helmer, a close friend of McCrae. After conducting Helmer’s burial service, McCrae poured his grief and exhaustion into verse while still tending the wounded. The poem appeared in Punch magazine that December and spread across the Allied world. Its power lay in its balance of mourning and resolve: the dead urge the living to fight on and remember. The poppy, blooming naturally on churned battlefields, became its central image of sacrifice and renewal. In Canada, Britain, and later across the Commonwealth, the poem’s words made the poppy the universal emblem of remembrance. McCrae never saw the Armistice, dying of pneumonia in January 1918, but his words became his memorial, echoed in ceremonies worldwide. The immense scale of wartime loss meant grief could not remain private. In Flanders Fields helped channel that sorrow into a shared ritual of remembrance, allowing families to locate their grief within a national story. Veterans’ groups and community leaders recognized its unifying power, encouraging rituals that allowed Canadians to honour the fallen together—a balance of comfort and burden that has allowed remembrance to endure through later traumas.

Image Description: This illustrated edition of In Flanders Fields was published in Ottawa in 1918 by the Heliotype Company, soon after McCrae’s death on active service. Here, The poem appears in a bordered window at lower right, naming McCrae as its Canadian author and noting his sacrifice. Around it stretches a stark battlefield and cemetery, with poppies in the foreground tinted in colour against muted sepia tones. The words dominate the composition, while the imagery amplifies their message: crosses recede into the distance, conveying the scale of loss, and bright poppies embody life rising from devastation. Reproduced widely in schools, veterans’ halls, and family homes, the poem became personal and collective memory. As Vimy Ridge became a symbol of military achievement, In Flanders Fields became the poem of remembrance—etched into memorials, recited each Remembrance Day, and uniting grief, memory, and renewal in a tradition that endures today.

Image Description: This illustrated edition of In Flanders Fields was published in Ottawa in 1918 by the Heliotype Company, soon after McCrae’s death on active service. Here, The poem appears in a bordered window at lower right, naming McCrae as its Canadian author and noting his sacrifice. Around it stretches a stark battlefield and cemetery, with poppies in the foreground tinted in colour against muted sepia tones. The words dominate the composition, while the imagery amplifies their message: crosses recede into the distance, conveying the scale of loss, and bright poppies embody life rising from devastation. Reproduced widely in schools, veterans’ halls, and family homes, the poem became personal and collective memory. As Vimy Ridge became a symbol of military achievement, In Flanders Fields became the poem of remembrance—etched into memorials, recited each Remembrance Day, and uniting grief, memory, and renewal in a tradition that endures today.

Explore Further:

Canadian War Museum - Remembrance, In Flanders’ FieldsCanadian Military History – Colonel John McCraeCanadian War Museum – Second Battle of YpresVeterans Affairs Canada – Poppy Campaign

CWM 19710261-0777, Canadian War Museum

The Battle of Vimy Ridge (9–12 April 1917) came at a moment when the First World War had already produced enduring symbols of modern industrial slaughter: chlorine gas at Second Ypres, futile losses on the Somme, and, later, the quagmire of Passchendaele. Yet in Canada’s case, Vimy rose above the rest, becoming the touchstone of national remembrance. Why Vimy? Beyond its tactical and strategic value, the battle became layered with symbolic meaning. The sight of Canadians fighting together as a unified Corps, succeeding where others had failed, offered a rare moment of triumph amid devastation. Newspapers seized on the victory immediately: on 11 April 1917, the Toronto Globe declared, “CANADIANS LEAD IN TRIUMPH,” celebrating the Corps’ “place of honour.” Canadians at the time already felt pride in their achievements, but few saw Vimy as the moment of Canada’s creation or as a uniquely unifying turning point. However, such framing cast Vimy as a symbol of Canada’s emerging confidence.

In the years that followed the First World War, as Canadians struggled to make sense of the sacrifice, this sense of distinction hardened into myth. Brigadier-General Alexander Ross, commanding the 28th Battalion, later recalled he had witnessed “the birth of a nation.” Reflected in Walter Allward’s 1936 memorial, erected as Canada’s national memorial in Europe, and popularized by Pierre Berton’s Vimy (1974), the idea took hold. Prime Ministers across the political spectrum have since echoed it, securing its place in public memory. The Canadian Corps’ decisive role in the Hundred Days of 1918 was just as crucial to Allied victory. Yet it is Vimy that continues to dominate the nation’s imagination. In this image, Canadian soldiers, bent under their gear, surge forward through torn earth and coils of wire as explosions fill the sky. The wire dominates the foreground, a visual barrier symbolizing the brutal defences of trench warfare.

The photograph was later retouched for wartime propaganda, adding mine explosions to heighten the drama and recall the massive charges detonated beneath the German lines at the attack’s outset. What we see is both record and construction: a glimpse of men pressing forward through wire and mud, but also an early shaping of Vimy’s memory into something larger than life. Unlike allegorical commemorative art, this image insists on lived experience—the wire, the mud, the bodies in motion—while hinting at how even “immediate” images carried symbolic weight.

In the years that followed the First World War, as Canadians struggled to make sense of the sacrifice, this sense of distinction hardened into myth. Brigadier-General Alexander Ross, commanding the 28th Battalion, later recalled he had witnessed “the birth of a nation.” Reflected in Walter Allward’s 1936 memorial, erected as Canada’s national memorial in Europe, and popularized by Pierre Berton’s Vimy (1974), the idea took hold. Prime Ministers across the political spectrum have since echoed it, securing its place in public memory. The Canadian Corps’ decisive role in the Hundred Days of 1918 was just as crucial to Allied victory. Yet it is Vimy that continues to dominate the nation’s imagination. In this image, Canadian soldiers, bent under their gear, surge forward through torn earth and coils of wire as explosions fill the sky. The wire dominates the foreground, a visual barrier symbolizing the brutal defences of trench warfare.

The photograph was later retouched for wartime propaganda, adding mine explosions to heighten the drama and recall the massive charges detonated beneath the German lines at the attack’s outset. What we see is both record and construction: a glimpse of men pressing forward through wire and mud, but also an early shaping of Vimy’s memory into something larger than life. Unlike allegorical commemorative art, this image insists on lived experience—the wire, the mud, the bodies in motion—while hinting at how even “immediate” images carried symbolic weight.

Explore Further:

Veterans Affairs Canada – The Battle of Vimy RidgeCanadian War Museum – Vimy RidgeLibrary and Archives Canada Blog – Vimy Ridge Journey of Maps

Library and Archives Canada, PA-001234

By August 1917, Canadian forces had become central to the Allied effort, called upon for demanding assaults like Hill 70 near Lens. The operation achieved its objective but at staggering cost: more than 9,000 Canadian casualties in under two weeks. For the wounded, survival began with the stretcher-bearers, who crossed shell-torn ground under fire, carrying men to

improvised dressing stations set up in ruined buildings like this one. There, medics worked quickly to stop bleeding and stabilize the injured before sending them further back. From these forward posts, the wounded might be carried to advanced dressing stations and then to casualty clearing stations where nursing sisters and surgeons worked together, often deep into the night, under relentless pressure. Some recovered and returned to their units; many were evacuated to base hospitals far from the front, while thousands never left the casualty stations alive. In this stream of care, women were central. Nursing sisters often worked under constant artillery or gas attack. Soldiers remembered them as a salve amid the chaos, their calm reassurance and tireless care a crucial comfort in extremis. But these women endured trauma too: they saw shattered bodies and received the disfigured and broken—faces mangled by shell fragments, lungs choked by gas, minds haunted by shock—and kept going, their compassion a quiet act of courage unmatched in civilian medical history.

Pictured here in the shadow of a shattered building, four stretcher-bearers work urgently over a wounded man, rolling him onto his side so his face, half-shadowed beneath their bodies, turns toward the camera. The tight frame leaves no escape from broken brick, splintered timber, and tracked mud, a reminder that this aid station sits only steps from the fighting. Hobnailed boots glint under a slick of clay; a discarded helmet lies nearby, mute evidence of those already carried away. Behind the group, another wounded soldier props himself on one elbow, watching as his comrade is treated, while another figure lays on a stretcher in the foreground. A soldier stands between these clusters, the gas-mask kit hanging on his chest an ever-present reminder of the insidious threat of chemical warfare. On the left, two figures lean together in conversation, their attention fixed elsewhere. Every element—bodies pressed together, cramped space, gear worn constantly—speaks to the urgency, unrelenting labour, and exhaustion of frontline care and the fragile boundary between life and loss.

improvised dressing stations set up in ruined buildings like this one. There, medics worked quickly to stop bleeding and stabilize the injured before sending them further back. From these forward posts, the wounded might be carried to advanced dressing stations and then to casualty clearing stations where nursing sisters and surgeons worked together, often deep into the night, under relentless pressure. Some recovered and returned to their units; many were evacuated to base hospitals far from the front, while thousands never left the casualty stations alive. In this stream of care, women were central. Nursing sisters often worked under constant artillery or gas attack. Soldiers remembered them as a salve amid the chaos, their calm reassurance and tireless care a crucial comfort in extremis. But these women endured trauma too: they saw shattered bodies and received the disfigured and broken—faces mangled by shell fragments, lungs choked by gas, minds haunted by shock—and kept going, their compassion a quiet act of courage unmatched in civilian medical history.

Pictured here in the shadow of a shattered building, four stretcher-bearers work urgently over a wounded man, rolling him onto his side so his face, half-shadowed beneath their bodies, turns toward the camera. The tight frame leaves no escape from broken brick, splintered timber, and tracked mud, a reminder that this aid station sits only steps from the fighting. Hobnailed boots glint under a slick of clay; a discarded helmet lies nearby, mute evidence of those already carried away. Behind the group, another wounded soldier props himself on one elbow, watching as his comrade is treated, while another figure lays on a stretcher in the foreground. A soldier stands between these clusters, the gas-mask kit hanging on his chest an ever-present reminder of the insidious threat of chemical warfare. On the left, two figures lean together in conversation, their attention fixed elsewhere. Every element—bodies pressed together, cramped space, gear worn constantly—speaks to the urgency, unrelenting labour, and exhaustion of frontline care and the fragile boundary between life and loss.

Explore Further:

Canadian War Museum – Medical TreatmentsOfficial History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War: Medical ServicesCanadian War Museum – Hill 70

Imperial War Museums, Q 1256

Artillery was the greatest killer of the First World War. Its relentless violence often left the dead disfigured and unrecognizable. Under such conditions, burial was done quickly and practically, sometimes even by battle-weary comrades or stretcher-bearers working under fire. Leaving bodies on the field was unthinkable: summer heat and constant shelling hastened decay, drawing flies and vermin, while the risk of disease and the sight of the dead weighed heavily on morale. Early in the war, graves registration was loosely organized, and burials were often improvised: shallow graves marked by helmets, rifles, rough wooden crosses, or stones. As the conflict dragged on, burial parties under Graves Registration Units gradually brought more structure and improved record-keeping. Still, many of the fallen remained unidentified. The improvised battlefield resting places reflected not only the brutality of war but also an imperfect human response: raw, fragile attempts to give meaning to unthinkable loss. For comrades in the field, these temporary graves were more than a necessity: they were small acts of dignity and remembrance. Soldiers returning to the front often found scattered markers dotting the churned earth, reminders that memory persisted even when identity could not. Many were later reinterred in permanent cemeteries under simple markers bearing the inscription:

“A Soldier of the Great War—Known Unto God.” In later years, the idea of the

unknown soldier gave national form to this personal grief. Tombs in capital cities from London to Ottawa became sites where collective memory met private mourning, and where families without a grave could still lay flowers, and a nation could honour the cost of war, even when names had been lost.

Here a simple wooden cross marks the grave of an unknown Canadian soldier, topped by a battered steel helmet. At its peak, someone has pencilled “R.I.P.”. Pale chalk stones outline the mound, stark against the churned mud—practical, minimal, and sorrowful. The grave lies raised on open ground, suggesting it was made hastily, perhaps within hours of death. This is a makeshift burial, placed where the soldier fell, a brief act of care before comrades moved on. Though simple, the helmet, stones, and pencilled letters give the grave weight, offering a fragile stand against anonymity amid the vast destruction of industrial war. His marker invites us to pause, to honour the unnamed, and to reflect on the life, service, and sacrifice behind this simple cross.

“A Soldier of the Great War—Known Unto God.” In later years, the idea of the

unknown soldier gave national form to this personal grief. Tombs in capital cities from London to Ottawa became sites where collective memory met private mourning, and where families without a grave could still lay flowers, and a nation could honour the cost of war, even when names had been lost.

Here a simple wooden cross marks the grave of an unknown Canadian soldier, topped by a battered steel helmet. At its peak, someone has pencilled “R.I.P.”. Pale chalk stones outline the mound, stark against the churned mud—practical, minimal, and sorrowful. The grave lies raised on open ground, suggesting it was made hastily, perhaps within hours of death. This is a makeshift burial, placed where the soldier fell, a brief act of care before comrades moved on. Though simple, the helmet, stones, and pencilled letters give the grave weight, offering a fragile stand against anonymity amid the vast destruction of industrial war. His marker invites us to pause, to honour the unnamed, and to reflect on the life, service, and sacrifice behind this simple cross.

Explore Further:

Canadian War Museum – The Unknown SoldierImperial War Museums - Image RecordDirectorate of History and Heritage – Memorials, Monuments, Cemeteries

William Rider-Rider / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library

and Archives Canada / PA-002715

and Archives Canada / PA-002715

By 1918, more than 2,800 Canadian Nursing Sisters served in England, across the Western Front in France and Belgium, and in the Eastern Mediterranean, tending to the wounded in casualty clearing stations, field hospitals, and base wards. They worked under relentless strain: operating within range of artillery fire and bombers, improvising amid shortages, and caring not only for shattered bodies but also for men disfigured, blinded, and mentally traumatized. Many soldiers later recalled their presence as a rare source of calm and dignity amid chaos. Yet for the nurses, the burden was immense: they bore witness to suffering on a scale few had imagined, often comforting the dying when families could not be there. As the war’s final offensives brought mounting casualties, Nursing Sisters became part of a broader continuum of care, one that extended beyond life into memory. After stabilizing the living and tending to the dead, many participated in small burial rites such as planting flowers, laying wreaths, and marking graves. These quiet gestures carried profound weight: personal acts of remembrance performed on devastated ground, where community and ceremony were fragile but essential.

In this image, three Nursing Sisters place flowers on rows of fresh graves. Their veils catch the light, lending their bowed figures a solemn grace amid the stark wooden crosses. The composition carries a quiet rhythm: the three women bend at different heights, forming a diagonal that draws the eye left to right, guiding us through their gestures of care. Behind them, a formation of soldiers stands with a brass band, instruments resting beneath their arms. The stillness carries weight; men and women pausing together in collective mourning before returning to duty. These same women who once steadied shaking hands in casualty stations now honour the fallen in death, their actions binding care to remembrance. Each small cluster of flowers softens the starkness of the wooden markers, lending dignity to these temporary graves so near to where so many had suffered. Through a narrow break in the figures, more crosses stretch into the distance, hinting at the greater scale of loss beyond the frame. Many similar wartime burials were later incorporated into larger military cemeteries, as the Imperial War Graves Commission transformed temporary resting places into carefully designed, permanent cemeteries. These improvised ceremonies offered solace and meaning at the source of grief, long before the national rituals of commemoration took form.

In this image, three Nursing Sisters place flowers on rows of fresh graves. Their veils catch the light, lending their bowed figures a solemn grace amid the stark wooden crosses. The composition carries a quiet rhythm: the three women bend at different heights, forming a diagonal that draws the eye left to right, guiding us through their gestures of care. Behind them, a formation of soldiers stands with a brass band, instruments resting beneath their arms. The stillness carries weight; men and women pausing together in collective mourning before returning to duty. These same women who once steadied shaking hands in casualty stations now honour the fallen in death, their actions binding care to remembrance. Each small cluster of flowers softens the starkness of the wooden markers, lending dignity to these temporary graves so near to where so many had suffered. Through a narrow break in the figures, more crosses stretch into the distance, hinting at the greater scale of loss beyond the frame. Many similar wartime burials were later incorporated into larger military cemeteries, as the Imperial War Graves Commission transformed temporary resting places into carefully designed, permanent cemeteries. These improvised ceremonies offered solace and meaning at the source of grief, long before the national rituals of commemoration took form.