Post-Second World War

The Korean War

The Korean War marked the beginning of a new era in Canadian military service. Five years after the end of the Second World War, Canada committed troops, ships, and aircraft to a United Nations (UN) coalition defending South Korea after the North’s sudden invasion across the 38 th Parallel in June 1950. The UN itself was barely five years old, and Korea became its first major test of collective action: a moment where Canada helped define what international cooperation would mean in a divided world. The first months brought sweeping reversals: UN forces driven back to the southern tip of the peninsula before surging north, only to face massive Chinese intervention by the winter of 1950. Over three years, Canadians fought in punishing terrain and extreme winters, through shifting front lines and long periods of stalemate. Unlike earlier conflicts, Korea unfolded in the shadow of the Cold War, a struggle of ideology as much as territory, signalling that Canada’s responsibilities were entering unfamiliar ground. More than 26,000 Canadians served: soldiers in relentless patrols, sailors navigating mine-strewn waters, and pilots flying dangerous missions in support of UN forces. The multinational nature of the war was new as well: 16 nations fought under UN command, integrating combat operations, naval support, medical evacuation, and humanitarian care. This experience foreshadowed the peacekeeping role Canada would later embrace under the UN flag.

By the time an armistice was signed on 27 July 1953, 516 Canadians had died and many more returned home changed. While lessons from earlier wars shaped medical and psychological care, Korea exposed new challenges. Rotational tours and sustained stress created invisible burdens, and many veterans faced limited recognition or support. These experiences helped shape how Canada would later confront the psychological costs of service. Often called Canada’s “Forgotten War,” Korea lacked the unifying narrative of a Vimy Ridge or Juno Beach and struggled for place in public memory. It ended without victory parades or decisive resolution, overshadowed by nuclear fears and later Cold War crises. Yet its legacy endures. Korea deepened Canada’s commitment to collective security, strengthened its international alliances, and broadened the meaning of service in a divided world.

By the time an armistice was signed on 27 July 1953, 516 Canadians had died and many more returned home changed. While lessons from earlier wars shaped medical and psychological care, Korea exposed new challenges. Rotational tours and sustained stress created invisible burdens, and many veterans faced limited recognition or support. These experiences helped shape how Canada would later confront the psychological costs of service. Often called Canada’s “Forgotten War,” Korea lacked the unifying narrative of a Vimy Ridge or Juno Beach and struggled for place in public memory. It ended without victory parades or decisive resolution, overshadowed by nuclear fears and later Cold War crises. Yet its legacy endures. Korea deepened Canada’s commitment to collective security, strengthened its international alliances, and broadened the meaning of service in a divided world.

Imperial War Museum, MH 033020

February 1951, the Korean War had entered a harsher phase. After UN forces drove the North Korean army back toward the Yalu River in late 1950, massive Chinese counter-offensives pushed them south again, turning the front into a bitter struggle for ridges, valleys, and frozen ground. Seeking to regain momentum, UN forces launched an offensive on 21 February to clear enemy troops south of the Han River and secure a defensible line near the 38th Parallel.

Into this advance came the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (2 PPCLI), serving in a Commonwealth brigade alongside British, Australian, New Zealand, and Indian units, a distinctly international effort early in the Cold War. On 22 February, in sleet and deep snow, “C” Company attacked a hilltop position where four Canadians were killed: Privates Kenneth O’Brien, Elliott MacKay, Thomas Colbourne, and James Calkins. O’Brien, nineteen years old, was carried toward a field ambulance but died en route. Their loss marked Canada’s first combat fatalities of the war. The first Canadian death in Korea, however, had come a month earlier: Regimental Sergeant Major James D. Wood was killed on 18 January 1951 while demonstrating mine-clearing techniques. His passing underscored that the hazards of service in Korea extended beyond the battle itself. This stark photograph captures a solemn moment on frozen ground. Four Commonwealth soldiers carry Private Kenneth O’Brien on a stretcher across rutted ice and churned mud; the same footing 2 PPCLI through in the attack. Look closely: One bearer has draped his coat over O’Brien for warmth, a simple gesture of care.

O’Brien never reached the aid post. In a war far from home, his quiet journey on the stretcher became one of Canada’s first combat sacrifices in Korea, borne silently by comrades before the news ever reached families across the ocean. It was an early reminder that endurance and loss would define the campaign ahead.

Into this advance came the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (2 PPCLI), serving in a Commonwealth brigade alongside British, Australian, New Zealand, and Indian units, a distinctly international effort early in the Cold War. On 22 February, in sleet and deep snow, “C” Company attacked a hilltop position where four Canadians were killed: Privates Kenneth O’Brien, Elliott MacKay, Thomas Colbourne, and James Calkins. O’Brien, nineteen years old, was carried toward a field ambulance but died en route. Their loss marked Canada’s first combat fatalities of the war. The first Canadian death in Korea, however, had come a month earlier: Regimental Sergeant Major James D. Wood was killed on 18 January 1951 while demonstrating mine-clearing techniques. His passing underscored that the hazards of service in Korea extended beyond the battle itself. This stark photograph captures a solemn moment on frozen ground. Four Commonwealth soldiers carry Private Kenneth O’Brien on a stretcher across rutted ice and churned mud; the same footing 2 PPCLI through in the attack. Look closely: One bearer has draped his coat over O’Brien for warmth, a simple gesture of care.

O’Brien never reached the aid post. In a war far from home, his quiet journey on the stretcher became one of Canada’s first combat sacrifices in Korea, borne silently by comrades before the news ever reached families across the ocean. It was an early reminder that endurance and loss would define the campaign ahead.

Explore Further:

Veterans Affairs Canada – The Korean WarLegion Magazine – The First to Fall in KoreaImperial War Museum – Kenneth O’Brien Photo Record

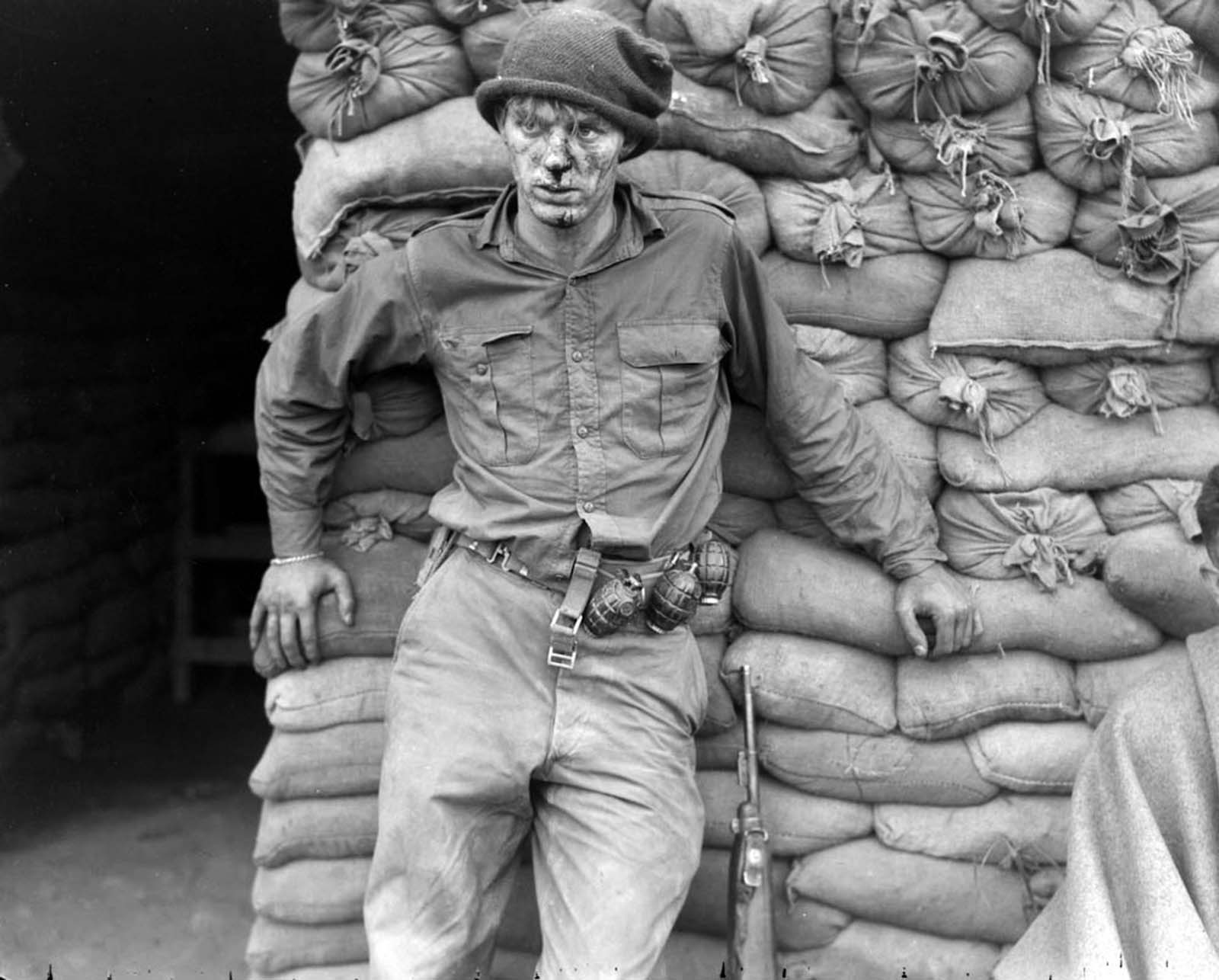

Paul E. Tomelin, Department of National Defence, PMR73-596

By mid-1952, Canadian soldiers were serving through one of the Korean War’s most punishing phases. The sweeping manoeuvres of 1950 had given way to a grinding stalemate along fortified lines. In this sector, Hill 355 (“Little Gibraltar”) became one of the war’s most contested positions, drawing repeated assaults and counterattacks through 1951 and 1952. Canadians endured freezing nights in bunkers, constant artillery fire, and the strain of endless patrols. Unlike the mass mobilizations of the World Wars, soldiers rotated through six- or twelve-month tours. This spread responsibility across the force, but placed prolonged strain on individuals. Many casualties came not in set battles, but in the steady toll of raids, ambushes, and sudden fire in the shadow of fortified ground. Medical evacuation improved survival rates, yet many returned home with lasting wounds, both visible and unseen. At the time, commanders spoke of “battle fatigue” or “operational exhaustion,” but understanding and support lagged far behind the reality endured by those on the line.

This photograph shows Private Heath Matthews, age 20, of “C” Company, 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment, wounded on 22 June 1952, after returning from a night patrol near Hill 166, close to Little Gibraltar.

Captured by Canadian war photographer Paul E. Tomelin, the image became one of the most enduring representations of Canada’s Korean War experience, later known simply as “The Face of War.” Matthews leans against a sandbagged bunker, his face streaked with blood, grime, and exhaustion. Grenades hang loosely from his belt, his rifle rests nearby, and his hands press into the wall for support. There is no pose or performance here, only a stark, unguarded moment suspended between action and aftermath. Tomelin’s lens avoids spectacle yet reveals something deeper: the toll of war etched into a single expression, the weight of suffering and endurance captured together.

This photograph shows Private Heath Matthews, age 20, of “C” Company, 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment, wounded on 22 June 1952, after returning from a night patrol near Hill 166, close to Little Gibraltar.

Captured by Canadian war photographer Paul E. Tomelin, the image became one of the most enduring representations of Canada’s Korean War experience, later known simply as “The Face of War.” Matthews leans against a sandbagged bunker, his face streaked with blood, grime, and exhaustion. Grenades hang loosely from his belt, his rifle rests nearby, and his hands press into the wall for support. There is no pose or performance here, only a stark, unguarded moment suspended between action and aftermath. Tomelin’s lens avoids spectacle yet reveals something deeper: the toll of war etched into a single expression, the weight of suffering and endurance captured together.

Explore Further:

Library and Archives Canada – Paul Tomelin Photo RecordVeterans Affairs Canada – The Korean War

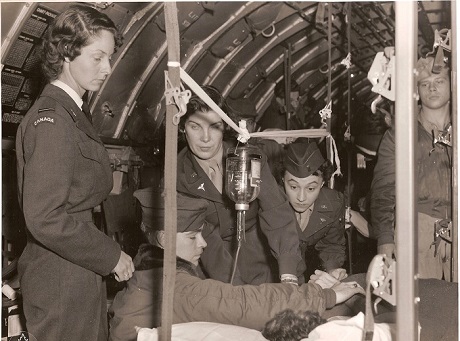

Department of National Defence, PL-144573

The Korean War marked a turning point in battlefield medicine. For the first time, large-scale air evacuation became routine, linking regimental aid posts, forward surgical units, and fully equipped rear hospitals in Japan. Helicopters and transport aircraft carried thousands of wounded to safety, reducing evacuation times from days to hours and dramatically improving survival rates.

Canadian soldiers were treated within this wider UN medical chain. They were stabilized by their unit medical officers, then moved through U.S.-led evacuation routes that included Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals (MASH) near the front and rear hospitals overseas. Canada’s own contribution came above all in the long-distance stages of this system. Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) crews of No. 426 Squadron maintained a trans-Pacific air bridge for troops and supplies, and carried casualties on the long journey home. Canadian flight nurses, including Flying Officer Joan Drummond, trained alongside United States Air Force (USAF) colleagues and cared for patients during long evacuation flights from Japan to Hawaii, California, and onward to Canada. Within Canada itself, RCAF Dakotas and other aircraft conducted “hospital flights,” ensuring that wounded soldiers reached facilities for recovery. These operations represented one of the earliest sustained uses of long-range aeromedical evacuation in Canadian history. They also brought Canadian women in uniform into demanding new roles closely tied to combat casualties.

Shown here inside the narrow fuselage of a transport aircraft, Flying Officer Joan Drummond (left) of the RCAF Nursing Service stands with USAF nurses as they tend to a wounded soldier. Improvised racks hold IV lines above stretcher patients who fill the cabin, turning the aircraft into an airborne ward assembled under pressure.

The calm concentration of the nurses conveys quiet professionalism amid urgency, reflecting the care and cooperation that sustained thousands of wounded soldiers on long, difficult journeys away from the battlefield. Beyond the frozen hills and fortified ridges of Korea, Canadians contributed not only through combat but also through the work of healing, carrying men from chaos toward safety and dignity. Today, images like this remind us that even a “Forgotten War” left indelible marks of sacrifice and care.

Canadian soldiers were treated within this wider UN medical chain. They were stabilized by their unit medical officers, then moved through U.S.-led evacuation routes that included Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals (MASH) near the front and rear hospitals overseas. Canada’s own contribution came above all in the long-distance stages of this system. Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) crews of No. 426 Squadron maintained a trans-Pacific air bridge for troops and supplies, and carried casualties on the long journey home. Canadian flight nurses, including Flying Officer Joan Drummond, trained alongside United States Air Force (USAF) colleagues and cared for patients during long evacuation flights from Japan to Hawaii, California, and onward to Canada. Within Canada itself, RCAF Dakotas and other aircraft conducted “hospital flights,” ensuring that wounded soldiers reached facilities for recovery. These operations represented one of the earliest sustained uses of long-range aeromedical evacuation in Canadian history. They also brought Canadian women in uniform into demanding new roles closely tied to combat casualties.

Shown here inside the narrow fuselage of a transport aircraft, Flying Officer Joan Drummond (left) of the RCAF Nursing Service stands with USAF nurses as they tend to a wounded soldier. Improvised racks hold IV lines above stretcher patients who fill the cabin, turning the aircraft into an airborne ward assembled under pressure.

The calm concentration of the nurses conveys quiet professionalism amid urgency, reflecting the care and cooperation that sustained thousands of wounded soldiers on long, difficult journeys away from the battlefield. Beyond the frozen hills and fortified ridges of Korea, Canadians contributed not only through combat but also through the work of healing, carrying men from chaos toward safety and dignity. Today, images like this remind us that even a “Forgotten War” left indelible marks of sacrifice and care.

Explore Further:

Veterans Affairs Canada – Women in ServiceCanadian Nursing Sisters in the Korean WarCold War and Peacekeeping Losses

The end of the Korean War did not mean an end to Canadian sacrifice overseas. Instead, new responsibilities emerged in a world marked by Cold War rivalry and the violence of regional wars. Canadian service in this era was shaped not by a single great campaign, but by vigilance, alliance, and the fragile demands of peace. Sailors, soldiers, and aircrew were called to guard distant seas, stand with NATO in Europe, and wear the blue helmets of the United Nations. These deployments were often less visible to the Canadian public than the world wars that preceded them, yet they carried real danger. For the navy and air force, the Cold War meant high-tempo training and constant readiness, where accidents could be as deadly as combat. For soldiers, UN duty placed them in contested regions where fighting had ceased but instability endured.

Peacekeeping became a defining part of Canada’s international identity, beginning with the Suez Crisis in 1956 and continuing through Cyprus, the Golan Heights, and many other missions. Yet the word “peace” was often misleading. Patrols took place in tense environments where violence could return without warning. In the Congo in the early 1960s, Canadians served in a civil war where secession and hostility claimed lives in a mission now largely forgotten at home. In Rwanda in the 1990s, Canadian personnel served amid genocide, their efforts constrained by weak mandates and the failure of international will, even as atrocities unfolded around them. Many returned carrying invisible wounds, with post-traumatic stress a lasting consequence of that mission. In the Balkans, they operated in volatile conditions marked by ethnic conflict and mass displacement, where international authority was fragile and the risks immediate. Such deployments showed that peacekeeping demanded courage not only under fire, but also in confronting atrocity and human suffering.

Service in these years asked much of Canadians but rarely commanded headlines at home. Losses came suddenly, in accidents at sea, in aircraft brought down by missiles, or on tense border patrols. Approximately 130 Canadians have died on peacekeeping operations since 1947, alongside others lost in Cold War service. The images on this panel speak to those realities. They show how sacrifice endured in an age described as a “Cold War” and in missions called “peacekeeping,” terms that implied safety, yet too often masked tragedy and loss.

Peacekeeping became a defining part of Canada’s international identity, beginning with the Suez Crisis in 1956 and continuing through Cyprus, the Golan Heights, and many other missions. Yet the word “peace” was often misleading. Patrols took place in tense environments where violence could return without warning. In the Congo in the early 1960s, Canadians served in a civil war where secession and hostility claimed lives in a mission now largely forgotten at home. In Rwanda in the 1990s, Canadian personnel served amid genocide, their efforts constrained by weak mandates and the failure of international will, even as atrocities unfolded around them. Many returned carrying invisible wounds, with post-traumatic stress a lasting consequence of that mission. In the Balkans, they operated in volatile conditions marked by ethnic conflict and mass displacement, where international authority was fragile and the risks immediate. Such deployments showed that peacekeeping demanded courage not only under fire, but also in confronting atrocity and human suffering.

Service in these years asked much of Canadians but rarely commanded headlines at home. Losses came suddenly, in accidents at sea, in aircraft brought down by missiles, or on tense border patrols. Approximately 130 Canadians have died on peacekeeping operations since 1947, alongside others lost in Cold War service. The images on this panel speak to those realities. They show how sacrifice endured in an age described as a “Cold War” and in missions called “peacekeeping,” terms that implied safety, yet too often masked tragedy and loss.

Naval Museum of Halifax, Department of National Defence, DND Archives, CT-11490

During the Cold War, the Royal Canadian Navy operated at high tempo: prepared always for training, readiness, and potential conflict. On 23 October 1969, HMCS Kootenay, a Restigouche-class destroyer, suffered a catastrophic gearbox explosion during full-power sea trials off the coast of Plymouth, England. Fire and toxic smoke raced through the ship, killing nine sailors and injuring over fifty. It was the worst peacetime accident in Canadian naval history.

At the time, Canadian military policy required that those who died on duty overseas be buried in the theatre of operations or the nearest Commonwealth cemetery. This reflected long-standing Commonwealth practice from the world wars, when repatriation of war dead was considered impractical due to scale and cost. For the Kootenay dead, families were given two choices: burial at sea or interment in England. Four sailors were buried at sea with full naval honours, four were laid to rest at Brookwood Military Cemetery in Surrey, and the ninth, Petty Officer Lewis John Stringer, died as the task group was returning to Canada and was buried in Halifax. The Kootenay disaster marked a turning point. Public reaction was sharp. Many Canadians were angered that the bodies were not brought home. The controversy helped drive a change in policy, and in 1970 the Canadian Forces adopted a new principle: from that point forward, service personnel who died abroad would be repatriated home to Canada for burial. Image Description: This photograph captures the formal funeral service on 27 October 1969, held aboard HMCS Saguenay, a sister ship in the same task force, while Kootenay lays burned and damaged in the background, moored at Devonport. Sailors stand in formation on deck, silent and solemn, as officers and chaplains conduct the rites of farewell.

The juxtaposition of Saguenay’s ordered ranks with Kootenay’s charred hull in the background underscores both discipline and loss. Naval tradition is visible in every detail: full honours, collective bearing, and the solemn dignity of farewell at sea. Though far from home, these rites connected the dead to Canada and marked a turning point: not only in shipboard safety and training, but also in how the nation would remember and repatriate its fallen.

At the time, Canadian military policy required that those who died on duty overseas be buried in the theatre of operations or the nearest Commonwealth cemetery. This reflected long-standing Commonwealth practice from the world wars, when repatriation of war dead was considered impractical due to scale and cost. For the Kootenay dead, families were given two choices: burial at sea or interment in England. Four sailors were buried at sea with full naval honours, four were laid to rest at Brookwood Military Cemetery in Surrey, and the ninth, Petty Officer Lewis John Stringer, died as the task group was returning to Canada and was buried in Halifax. The Kootenay disaster marked a turning point. Public reaction was sharp. Many Canadians were angered that the bodies were not brought home. The controversy helped drive a change in policy, and in 1970 the Canadian Forces adopted a new principle: from that point forward, service personnel who died abroad would be repatriated home to Canada for burial. Image Description: This photograph captures the formal funeral service on 27 October 1969, held aboard HMCS Saguenay, a sister ship in the same task force, while Kootenay lays burned and damaged in the background, moored at Devonport. Sailors stand in formation on deck, silent and solemn, as officers and chaplains conduct the rites of farewell.

The juxtaposition of Saguenay’s ordered ranks with Kootenay’s charred hull in the background underscores both discipline and loss. Naval tradition is visible in every detail: full honours, collective bearing, and the solemn dignity of farewell at sea. Though far from home, these rites connected the dead to Canada and marked a turning point: not only in shipboard safety and training, but also in how the nation would remember and repatriate its fallen.

Explore Further:

Department of National Defence – The HMCS Kootenay Explosion52 Years On, Survivors and Family Remember HMCS KootenayLegion Magazine – “Disaster aboard HMCS Kootenay”

Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum

After the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the United Nations created new peacekeeping missions to stabilise the Middle East. Canada was central to this effort. Canadian soldiers, pilots, and support staff served with the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF II) in Egypt and the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) in Syria, monitoring ceasefires and manning observation posts along tense frontiers. The Royal Canadian Air Force supplied critical airlift capacity, flying Buffalo and other transport aircraft in the distinctive white and blue of the UN. These flights carried supplies, equipment, and personnel between fragile buffer zones and regional capitals. In a region where ceasefires could collapse without warning, even unarmed missions exposed peacekeepers to real risk. On 9 August 1974, a Canadian Buffalo aircraft, serving with 116 Air Transport Unit, was shot down by Syrian surface-to-air missiles while flying from Ismailia, Egypt, via Beirut to Damascus on UN duty. All nine Canadians aboard were killed. The tragedy shocked the nation and remains the single deadliest day in Canadian peacekeeping history. Two other Canadians serving in Cyprus were also killed that same month, making August 1974 the deadliest in Canada’s peacekeeping story. In 2008, 9 August was officially designated National Peacekeepers’ Day, ensuring their sacrifice would be formally remembered.

The photograph shows a restored Canadian Buffalo transport aircraft, painted in UN white and preserved today as Buffalo 461. Its simple lines belie the danger of the mission it once flew. For Canadians, it serves as a living memorial, a tangible link between those who were lost and the ongoing story of service.

Though quiet in appearance, the story behind the image is one of profound loss. The Buffalo Nine became a national symbol of the hazards of peacekeeping in contested skies and unstable regions. Their sacrifice is honoured in annual commemorations, in preserved aircraft displays, and in memorials across Canada. The Buffalo Nine remind us that peacekeeping, though rooted in diplomacy and restraint, carried real peril, and that those who served in its cause accepted risks as great as those faced in combat.

The photograph shows a restored Canadian Buffalo transport aircraft, painted in UN white and preserved today as Buffalo 461. Its simple lines belie the danger of the mission it once flew. For Canadians, it serves as a living memorial, a tangible link between those who were lost and the ongoing story of service.

Though quiet in appearance, the story behind the image is one of profound loss. The Buffalo Nine became a national symbol of the hazards of peacekeeping in contested skies and unstable regions. Their sacrifice is honoured in annual commemorations, in preserved aircraft displays, and in memorials across Canada. The Buffalo Nine remind us that peacekeeping, though rooted in diplomacy and restraint, carried real peril, and that those who served in its cause accepted risks as great as those faced in combat.

Explore Further:

Vintage Wings of Canada – The Buffalo NineRoyal Aviation Museum of Western Canada – RememberingThe United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF)

Image Credit: Department of National Defence, MEC76-14

In 1974, following the Yom Kippur War, Canada committed troops to the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) in the Golan Heights. For the next three decades, Canadians rotated through this mission, joining other UN contingents to monitor the ceasefire line between Israel and Syria. Their role was not combat but vigilance: manning observation posts, running patrols, and reporting violations that might reignite war.

Peacekeeping in the Golan exemplified the discipline and restraint expected of Canadian troops in the Cold War era. Soldiers operated under strict rules of engagement, often lightly armed, yet their presence was essential to holding the ceasefire intact. White UN vehicles and blue berets became visible symbols of neutrality, reminders to civilians and combatants alike that the world was watching. Canadians served in more than fifty UN missions worldwide, including every mission until 1989, with the Golan Heights one of the longest-running commitments. For most personnel, the defining experience was the long vigil on the ground—enduring heat and cold, separation from family, and the quiet strain of service in a region where peace was fragile. Losses did occur: Canadians died in vehicle accidents, landmine incidents, and other hazards of service, a reality that stood in stark contrast to the popular image of peacekeeping as safe or bloodless duty.

Pictured here: Canadian peacekeepers with their armoured personnel carrier in the Golan Heights in 1976, painted white and marked with bold UN letters. There is little drama in the scene: a dusty road, a vehicle, and men on patrol. Yet the ordinariness is deceptive. These were the daily rhythms of peacekeeping: monotonous, watchful, and demanding constant discipline. The white-painted carrier and blue-helmeted troops signalled neutrality, but also embodied risk: Canadians were present in a contested land, trusted to hold a ceasefire that could collapse without warning. In its quiet way, the image honours the commitment and sacrifice that makes peacekeeping one of the most enduring chapters of Canada’s military story.

Peacekeeping in the Golan exemplified the discipline and restraint expected of Canadian troops in the Cold War era. Soldiers operated under strict rules of engagement, often lightly armed, yet their presence was essential to holding the ceasefire intact. White UN vehicles and blue berets became visible symbols of neutrality, reminders to civilians and combatants alike that the world was watching. Canadians served in more than fifty UN missions worldwide, including every mission until 1989, with the Golan Heights one of the longest-running commitments. For most personnel, the defining experience was the long vigil on the ground—enduring heat and cold, separation from family, and the quiet strain of service in a region where peace was fragile. Losses did occur: Canadians died in vehicle accidents, landmine incidents, and other hazards of service, a reality that stood in stark contrast to the popular image of peacekeeping as safe or bloodless duty.

Pictured here: Canadian peacekeepers with their armoured personnel carrier in the Golan Heights in 1976, painted white and marked with bold UN letters. There is little drama in the scene: a dusty road, a vehicle, and men on patrol. Yet the ordinariness is deceptive. These were the daily rhythms of peacekeeping: monotonous, watchful, and demanding constant discipline. The white-painted carrier and blue-helmeted troops signalled neutrality, but also embodied risk: Canadians were present in a contested land, trusted to hold a ceasefire that could collapse without warning. In its quiet way, the image honours the commitment and sacrifice that makes peacekeeping one of the most enduring chapters of Canada’s military story.

Explore Further:

Veterans Affairs Canada – Canada and International Peacekeeping Canadian War Museum – Canada and Peacekeeping OperationsThe United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF)Afghanistan

The war in Afghanistan became Canada’s largest and longest military mission since Korea. From 2001 to 2014, more than 40,000 Canadian Armed Forces personnel served there, deploying to Kabul, Kandahar, and other regions as part of the international effort to confront terrorism and support stability in a country scarred by decades of conflict. What began as a limited intervention to deny sanctuary to al-Qaeda in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, attacks on New York and Washington evolved into a long struggle against insurgency. The war was carried out in harsh terrain, searing heat, bitter cold, amid dust that clogged both lungs and machinery, and among vulnerable communities where the line between danger and daily life was often unclear.

Canadians in Afghanistan fought in combat operations, trained Afghan forces, and supported reconstruction and development. Kandahar Province, where Canada took primary responsibility from 2005, was one of the war’s most volatile regions. Soldiers confronted roadside bombs, ambushes, and the constant strain of patrols where danger was often invisible until the moment it struck. Improvised explosive devices, hidden along roadsides and paths, were the most feared hazard of the war, accounting for most Canadian combat deaths. At its peak, Canada maintained a battle group, special operations forces, and supporting units, all operating under conditions that tested endurance and resilience in a mission without easy end.

The toll was heavy. One hundred and fifty-eight Canadians were killed, and thousands more were wounded, many carrying physical and psychological injuries that never fully healed. Their names joined those of earlier generations in the Books of Remembrance, each sharing an equal place of honour. Afghanistan also reshaped how Canadians mourned. Unlike earlier conflicts, its casualties unfolded in the age of instant communication, when news travelled quickly and images of ramp ceremonies were shared across the country. These public moments of tribute became new rituals of national remembrance, carrying military loss into the fabric of civic life.

The images on this panel reflect that dual reality: service amid the dust and danger of a distant war, and remembrance carried into Canadian communities far from the battlefield. They speak not only of combat and sacrifice, but also of how a nation chose to remember: standing together on bridges and roadsides, ensuring that each loss was marked, each name honoured, and each life carried into Canada’s collective memory.

Canadians in Afghanistan fought in combat operations, trained Afghan forces, and supported reconstruction and development. Kandahar Province, where Canada took primary responsibility from 2005, was one of the war’s most volatile regions. Soldiers confronted roadside bombs, ambushes, and the constant strain of patrols where danger was often invisible until the moment it struck. Improvised explosive devices, hidden along roadsides and paths, were the most feared hazard of the war, accounting for most Canadian combat deaths. At its peak, Canada maintained a battle group, special operations forces, and supporting units, all operating under conditions that tested endurance and resilience in a mission without easy end.

The toll was heavy. One hundred and fifty-eight Canadians were killed, and thousands more were wounded, many carrying physical and psychological injuries that never fully healed. Their names joined those of earlier generations in the Books of Remembrance, each sharing an equal place of honour. Afghanistan also reshaped how Canadians mourned. Unlike earlier conflicts, its casualties unfolded in the age of instant communication, when news travelled quickly and images of ramp ceremonies were shared across the country. These public moments of tribute became new rituals of national remembrance, carrying military loss into the fabric of civic life.

The images on this panel reflect that dual reality: service amid the dust and danger of a distant war, and remembrance carried into Canadian communities far from the battlefield. They speak not only of combat and sacrifice, but also of how a nation chose to remember: standing together on bridges and roadsides, ensuring that each loss was marked, each name honoured, and each life carried into Canada’s collective memory.

Silvia Pecota, Fallen: Task force Afghanistan, 2006.

Canadian service in Afghanistan was defined less by sweeping battles than by the relentless rhythm of patrols across villages, roads, and desert plains. Each movement carried its own hazards: ambushes from hidden positions, mortar and rocket fire arcing in from afar, and above all improvised explosive devices buried beneath dust and stone. Most Canadian combat deaths came not in large engagements but during routine missions, where the line between ordinary movement and mortal risk could vanish in an instant. The burden was both physical and mental: soldiers carried heavy loads through searing heat and bitter cold, nerves sharpened by uncertainty, lungs filled with dust. The desert horizon, so open in appearance, offered no safety: every culvert, every ridge, every skyline might conceal attack.

Amid this strain, soldiers forged bonds of endurance and care. Connection was found not only with Afghan civilians and comrades beside them, but also in the improvised rituals of mourning, tributes which reminded all that sacrifice would not be forgotten. Afghanistan is remembered less as a single campaign than as the cumulative strain of countless patrols: endurance, danger, camaraderie, and loss carried across a landscape where service was isolating and deeply human. Image Description: This artwork distills those realities through layered symbolism. In the foreground, a helmet and gear, adorned with a small Canadian flag, form a battlefield cross: an improvised tribute to loss recalling practices of earlier wars. Behind it, two soldiers walk into the desert. They suggest spirits, evoking the memory of Canadians lost in Afghanistan and the comradeship that endures beyond life. Their departure evokes loss, but also fellowship: no soldier falls or walks alone. In the distance, a Light Armoured Vehicle (LAV) stands silhouetted on the horizon. Around it, faint figures gather, not a patrol forming up, but the presence of those who had already fallen. They appear as a welcoming company, a spiritual vision of continuity in which the bonds of service extend even into death.

The setting remains stark: wide sky, empty ground, and no sign of relief. Yet within this barrenness, the red-and-white flag becomes a vivid counterpoint, a symbol of remembrance that ties sacrifice abroad to memory at home. In its

composition, the artwork moves between the physical and the spiritual, inviting viewers to reflect not only on Afghanistan’s terrain of danger and endurance, but also on the enduring fellowship of those who served and fell.

Amid this strain, soldiers forged bonds of endurance and care. Connection was found not only with Afghan civilians and comrades beside them, but also in the improvised rituals of mourning, tributes which reminded all that sacrifice would not be forgotten. Afghanistan is remembered less as a single campaign than as the cumulative strain of countless patrols: endurance, danger, camaraderie, and loss carried across a landscape where service was isolating and deeply human. Image Description: This artwork distills those realities through layered symbolism. In the foreground, a helmet and gear, adorned with a small Canadian flag, form a battlefield cross: an improvised tribute to loss recalling practices of earlier wars. Behind it, two soldiers walk into the desert. They suggest spirits, evoking the memory of Canadians lost in Afghanistan and the comradeship that endures beyond life. Their departure evokes loss, but also fellowship: no soldier falls or walks alone. In the distance, a Light Armoured Vehicle (LAV) stands silhouetted on the horizon. Around it, faint figures gather, not a patrol forming up, but the presence of those who had already fallen. They appear as a welcoming company, a spiritual vision of continuity in which the bonds of service extend even into death.

The setting remains stark: wide sky, empty ground, and no sign of relief. Yet within this barrenness, the red-and-white flag becomes a vivid counterpoint, a symbol of remembrance that ties sacrifice abroad to memory at home. In its

composition, the artwork moves between the physical and the spiritual, inviting viewers to reflect not only on Afghanistan’s terrain of danger and endurance, but also on the enduring fellowship of those who served and fell.

Explore Further:

Department of National Defence – Canada in Afghanistan (2001-2014)Government of Canada – The Canadian Army in Afghanistan

Department of National Defence, IS2009-1140

The war in Afghanistan brought not only combat and endurance but also new rituals of mourning. When a Canadian soldier was killed, comrades gathered for a ramp ceremony: a solemn farewell held on the tarmac before the fallen was flown home. Under desert sun or night floodlights, the military community paused its work to honour sacrifice in theatre. These ceremonies carried forward a long tradition of care for the dead. In earlier wars, soldiers buried comrades near the battlefield, raising wooden crosses or marking graves with what lay at hand. By the Second World War, formal cemeteries overseas gave permanence to that duty. In Afghanistan, repatriation was possible, yet the principle endured: comrades shouldered the casket, chaplains spoke prayers, and the presence of all ranks affirmed that no one fell alone.

This photograph shows the nighttime ramp ceremony at Kandahar Airfield following the death of Master Corporal Francis Reginald Roy on 25 June 2011. A Canadian C-17 Globemaster transport aircraft waits with its ramp lowered beneath soft floodlights, ready to receive the flag-draped casket. A contingent of pallbearers carries MCpl Roy’s coffin forward, their measured, steady movement elevating a duty into ritual honour.

More than 2,000 NATO troops (primarily Roy’s Canadian comrades) gathered that night, one of the largest such ceremonies at Kandahar. Soldiers stood in formation, weapons set aside, heads bowed. For a moment, the routines of war gave way to collective mourning, uniting ranks and units in a single gesture of respect. The casket at the centre drew every eye, from those present on the tarmac to the nation back home that would later bear witness through shared images.

In its stark simplicity, the ceremony embodied both grief and resolve. It continued a lineage of military remembrance, from improvised battlefield burials to structured rites of repatriation, each seeking to grant dignity to loss. In Afghanistan, ramp ceremonies became the defining ritual of mourning, ensuring that every fallen soldier was honoured among those who had marched beside them first, before beginning the final journey home.

This photograph shows the nighttime ramp ceremony at Kandahar Airfield following the death of Master Corporal Francis Reginald Roy on 25 June 2011. A Canadian C-17 Globemaster transport aircraft waits with its ramp lowered beneath soft floodlights, ready to receive the flag-draped casket. A contingent of pallbearers carries MCpl Roy’s coffin forward, their measured, steady movement elevating a duty into ritual honour.

More than 2,000 NATO troops (primarily Roy’s Canadian comrades) gathered that night, one of the largest such ceremonies at Kandahar. Soldiers stood in formation, weapons set aside, heads bowed. For a moment, the routines of war gave way to collective mourning, uniting ranks and units in a single gesture of respect. The casket at the centre drew every eye, from those present on the tarmac to the nation back home that would later bear witness through shared images.

In its stark simplicity, the ceremony embodied both grief and resolve. It continued a lineage of military remembrance, from improvised battlefield burials to structured rites of repatriation, each seeking to grant dignity to loss. In Afghanistan, ramp ceremonies became the defining ritual of mourning, ensuring that every fallen soldier was honoured among those who had marched beside them first, before beginning the final journey home.

Explore Further:

Legion Magazine – The Way HomeDepartment of National Defence – Canada in Afghanistan (2001-2014)Government of Canada – The Canadian Army in Afghanistan

Pete Fisher / Nesphotos.ca

Canada’s war in Afghanistan gave rise to a new ritual of remembrance that linked sacrifice abroad to mourning at home. When a soldier was killed in theatre, the process began with a ramp ceremony in Kandahar, followed by repatriation through 8 Wing Trenton, Ontario. From there, a convoy carried the fallen along Highway 401 to the coroner’s office in Toronto, a mandatory step before families and regiments could complete the rites of burial. This 172-kilometre route became known as the “Highway of Heroes.” From 2002 onward, citizens gathered spontaneously on overpasses to bear witness. They stood in silence, waved flags, and saluted passing convoys, transforming an ordinary stretch of highway into a living memorial. The practice quickly became embedded in national life: the route was officially named in 2007, bridge plaques later installed, and a tree-planting campaign has extended the tribute into a permanent living memorial.

The Highway of Heroes echoed earlier traditions—from Decoration Day after the Fenian Raids to the Vimy pilgrimages and the cenotaph ceremonies of Remembrance Day on 11 November. Yet it also marked something distinct: for the first time, Canadians witnessed in real time the return of their war dead, narrowing the distance between military sacrifice abroad and public mourning at home. The people who stood on the bridges bore witness for the nation, ensuring that no return passed in silence.

The photograph shows a convoy’s passage beneath a bridge crowded with Canadians. Uniformed officers salute, families raise flags, and strangers stand shoulder to shoulder in silence. Below, the hearses move steadily along the highway. The scene is ordinary (a highway and a bridge) yet profoundly transformed. It embodies how modern Canada came to remember in a new century: through public witness, collective grief, and symbolic acts of respect.

The Highway of Heroes joined Canada’s longer tradition of remembrance, from improvised battlefield crosses to Commonwealth cemeteries, from cenotaphs in town squares to national memorials. Here, remembrance lived not only in stone but in people: Canadians who stood together, bridge by bridge, to honour sacrifice.

The Highway of Heroes echoed earlier traditions—from Decoration Day after the Fenian Raids to the Vimy pilgrimages and the cenotaph ceremonies of Remembrance Day on 11 November. Yet it also marked something distinct: for the first time, Canadians witnessed in real time the return of their war dead, narrowing the distance between military sacrifice abroad and public mourning at home. The people who stood on the bridges bore witness for the nation, ensuring that no return passed in silence.

The photograph shows a convoy’s passage beneath a bridge crowded with Canadians. Uniformed officers salute, families raise flags, and strangers stand shoulder to shoulder in silence. Below, the hearses move steadily along the highway. The scene is ordinary (a highway and a bridge) yet profoundly transformed. It embodies how modern Canada came to remember in a new century: through public witness, collective grief, and symbolic acts of respect.

The Highway of Heroes joined Canada’s longer tradition of remembrance, from improvised battlefield crosses to Commonwealth cemeteries, from cenotaphs in town squares to national memorials. Here, remembrance lived not only in stone but in people: Canadians who stood together, bridge by bridge, to honour sacrifice.